The Stateless Diplomat

Mimi Malayan is Diana Apcar’s great-granddaughter. Since 2004, she has been researching her great-grandmother’s life and writings, in an effort to create an extensive archive, including photographs, documents, and memoirs by Armenian refugees in Japan.

The one thing most people think they know about Diana Agabeg Apcar is that she was “the first female diplomat”, and yet that statement is incorrect. Her accomplishments are enormous and extremely impressive; however, her appointment as Honorary Consul to Japan from Armenia in 1920 was never recognised by the Japanese government, denying her the official title. Despite that, for over a decade, before and after her appointment, she worked tirelessly on behalf of the Armenian people, rescuing around 2000 refugees escaping genocide who intended to emigrate to the United States. She also wrote ten books, around 100 articles and hundreds of letters to peace activists, humanitarian organisations, religious leaders, politicians and individuals, whom she believed might influence political action in support of persecuted Armenians under Ottoman rule.

Born in 1859 in Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar), Diana lived most of her early years within the Armenian diaspora of Calcutta (Kolkata). She attended convent school during her early years but her father’s death when she was just fourteen and other financial troubles, meant that much of her education was self-taught. After her mother’s death, when Diana was twenty-two, she returned to Rangoon to live with a sister and her family. Diana was a voracious reader and wrote her first novel as a young woman. “Susan” is a coming-of-age story about a young Indian Armenian woman struggling to choose the right husband.

On 18 June 1889, Diana and Armenian entrepreneur Michael Apcar married at St John the Baptist Armenian Apostolic Church in Rangoon. The following year the couple moved with their infant daughter, Rose, to Japan, a country recently opened to the world and bursting with opportunities for new businesses. The couple had five children, but two of their three sons died. After two bankruptcies Michael suddenly died in 1906, leaving Diana with debts and three children in a foreign land. Rather than return to Burma, Diana chose to redeem her husband’s debts. The family struggled, but she stabilised the business, making it successful within a few years.

In 1909, the Adana Massacres of Armenians in southwestern Anatolia prompted Diana to activism. While the weakening Ottoman Empire was losing one province after another, as Greece, Bulgaria, and Macedonia slipped away during the 19th century, the suspicion and hostility of the Ottoman government towards its remaining minorities steadily grew. The Hamidan Massacres of 1894-97, followed by Adana in 1909, resulted in 100,000 deaths; however, neither the Sublime Porte nor European Powers, actively meddling in Ottoman affairs, did anything to improve the situation for Armenians. So, Diana put her pen to paper, writing feverishly for several years, and publishing six books arguing for Armenian self-determination. She wrote a book a year, appealed to peace societies and sent her articles to major European and American newspapers, pleading her case: Armenians’ right for “security of life and property on the soil of their own country.” She corresponded with Stanford University founder David Starr Jordan, President of Columbia University Nicholas M Butler, US Secretary of State Robert Lansing, and dozens of others – academics, journalists, missionaries, and politicians. A hundred years before the emergence of social media, Diana had created an extensive network of connections, arguing repeatedly that if nothing were done to protect the Armenians, new massacres would be an inevitable outcome.

Her efforts were in vain. The Armenian Genocide of 1915 surpassed her worst predictions. One and a half million people were killed; hundreds of thousands of survivors fled in all directions to Syria, Lebanon, Europe, and the Caucasus. Some of them continued north into Russia, only to find that country enveloped in the bloody Bolshevik revolution. The refugees couldn’t go back and couldn’t travel west to Europe where World War I was raging. They chose an unexpected direction – East, taking the Trans-Siberian Railway all the way to Vladivostok on the Pacific Ocean. It took most refugees months, as they would frequently disembark the train to earn funds which enabled them to continue their journey. From Vladivostok the refugees had to get to Japan, Korea or China to sail to America. This is where they sought Diana’s help, to gain temporary asylum in Japan.

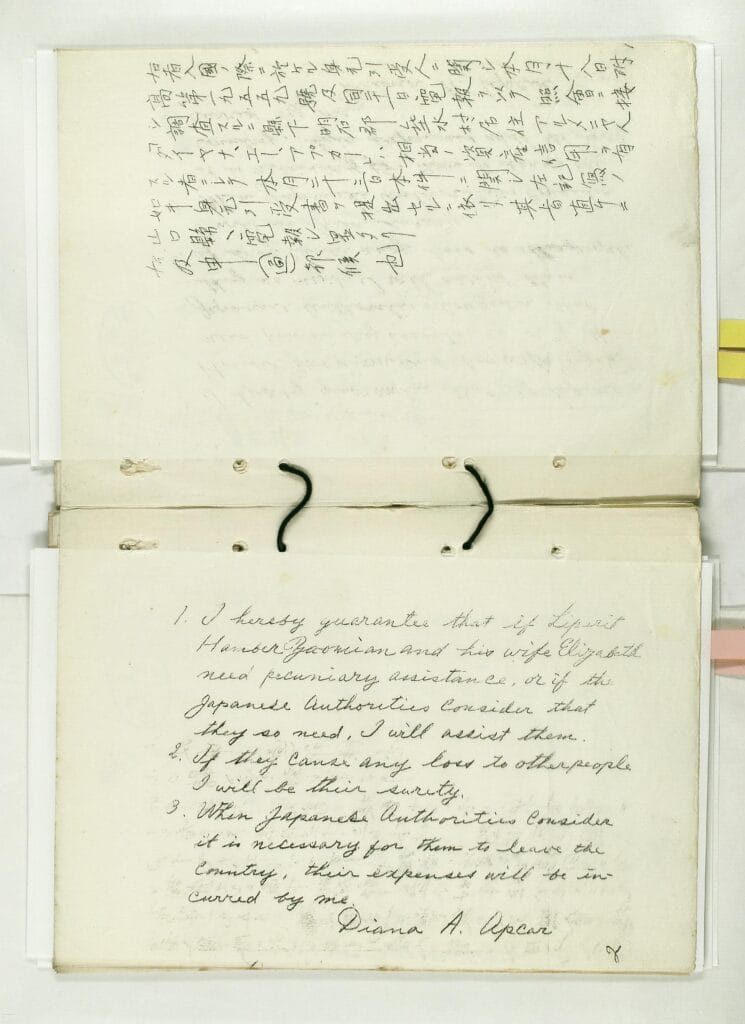

As Japan and the Ottoman Empire were on opposing sides during World War One, refugees with Ottoman passports were denied entry to Japan and were labelled “enemy combatants.” Diana argued with the Japanese Foreign Ministry, stating that the Armenians were not Turks and had in fact been victimised by the Ottoman regime. For refugees without sufficient funds to meet the Japanese visa requirements, Diana provided authorities with “guarantees” for their financial security. She rented houses to shelter them, found them jobs, and enrolled their children in school. When the American Red Cross opened in Vladivostok in 1917, Diana became the “manager” of the Armenians. Once the refugees reached Japan, Diana coordinated the next phase of their ordeal: she located their relatives in the United States or found them sponsors. She assisted the genocide survivors with their identification documents and fiercely negotiated with the steamship companies for passage, booked beyond capacity for months ahead as so many vessels had been reassigned to serve in the war effort. Using her own resources to help these lost souls, Diana was acting as a de facto ambassador of the lost nation of Armenia.

In 1918 Turkey was on the losing side of World War I and Russia was embroiled in its own civil war. This created a power vacuum in the Caucasus allowing for a new country to emerge. On May 28th, 1918, the First Republic of Armenia declared its independence. The country was impoverished and overrun by hundreds of thousands of refugees. Without outside support, it was destined to fail. However, in July 1920, in recognition of her service to the Armenian people, Armenia’s Prime Minister Hamo Ohanjanyan appointed Diana Apcar as Honorary Consul to Japan, the first woman to ever be appointed to that post and one of the first female diplomats to be appointed anywhere in the world. Sadly, while the Japanese government debated issues concerning her appointment, it failed to accept her as Honorary Consul before the Armenian Republic’s collapse. In November 1920, it was absorbed into what would become the Soviet Union. Despite this disappointment, Diana continued her work helping refugees, well into the mid-1920s, aiding and enabling approximately 2000 people in their quest for a new life.

Both Diana and the refugees shared a vision and a hope – no matter how unrealistic – that they would overcome their obstacles: that with hard work, perseverance, and a little human compassion they would succeed. Their battles were for their own survival, and that of a people and culture, despite the formidable odds against them.

Find out more about Diana Apcar here.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.