The Tiramisu Mountains: When Seas Vanish and Landscapes Are Born

Daniel Kordan is an internationally renowned photographer who runs photography workshops, tours and expeditions around the world

Around four billion years ago, Earth’s oceans formed – born from frozen water delivered by cosmic bodies and from condensed steam that fell as endless rain. From that moment, nothing on this planet has stood still. Today, oceans cover 71 percent of Earth’s surface. Tomorrow, that figure will shift again, for life on Earth is in constant motion.

We can see the atmosphere move in the passing of clouds. The lithosphere – the rigid outer crust of our planet – also shifts, but at a pace we cannot perceive: about the same rate our fingernails grow. These subtle yet unstoppable movements raise mountains, landscapes so fantastical they resemble layer cakes crafted by an Italian pastry god – tiramisus designed for giants.

It is the vast timescales that make such landscapes appear unreal. Our human lives are too brief to grasp their making. The striped “Tiramisu Mountains” in western Kazakhstan, for example, were once seabed. They were born of oceanic crust, just as the Alps, the Andes, the Dolomites, and even the plains of northern Germany once lay beneath the sea.

But if mountains come from oceans, a question emerges: where has all the water gone?

How a Sea Disappears

There are two fundamental ways a sea can vanish so completely it seems as though it never existed. Both are tectonic in origin – products of Earth’s restless crust.

Imagine Earth as a filled chocolate truffle. The crust is the brittle chocolate shell, while the mantle beneath is the molten caramel. The deeper you go, the hotter it becomes – roughly 30 degrees Celsius for every kilometer. By 30 or 40 kilometers down, temperatures exceed 1,200 degrees, and the mantle behaves like a viscous fluid. It drifts, wells upward in places, and reshapes the surface.

When tectonic motion isolates a marine basin from its supply of fresh water, and if that basin lies in an arid climate, evaporation can be complete.

The other path to oblivion comes through subduction. Not all crust is equal: oceanic crust is basalt, denser and heavier than the continental crust made of granite. Because basalt sinks deeper, it naturally holds water above it – the sea. But where oceanic crust is forced beneath a continent, the ocean shrinks. Basin after basin disappears until landmasses collide. The collision folds and uplifts whatever lies between, giving rise to mountain ranges like the Himalayas – born when India rammed into Eurasia – or the Alps, the result of Africa’s collision with Europe.

From Ocean Floor to Tiramisu

When tectonic plates shifted again, part of the Paleo-Tethys was trapped. The Caspian Basin was cut off, while slabs of oceanic crust slid under continents. Landmasses collided. Waters evaporated.

In the process, a chemical sequence unfolded. Clays and limestones dissolved and settled in orderly layers. At the bottom: clay. Above: limestone. Lighter chalk beds alternated with iron-rich reddish layers, and other minerals tinted the strata in hues of ochre, cream, and brown. The result was a natural tiramisu.

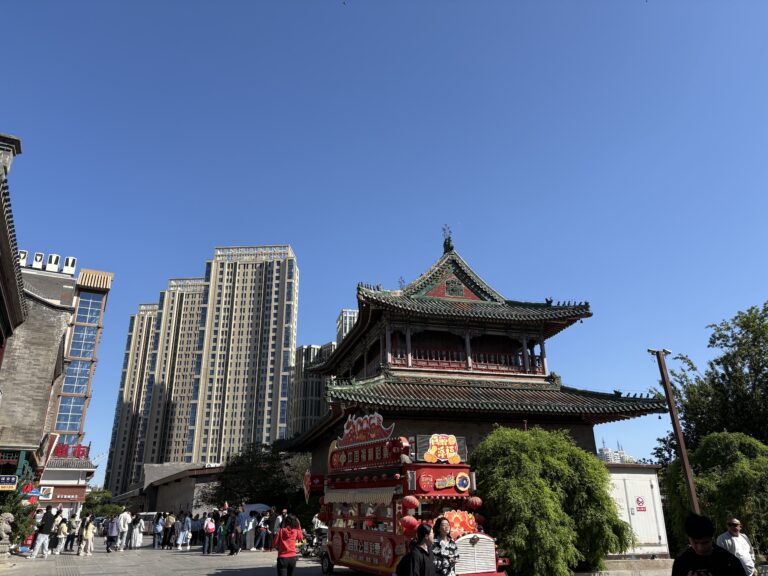

Today, these “Tiramisu Mountains” rise from the Mangystau region of western Kazakhstan. They are not towering peaks but low hills, 10 to 30 meters high, spread across an area of roughly eight by ten kilometers. “The sediment layers lie neatly stacked, one atop another – not tilted or broken, but gently lifted by the collision of plates,” explains Christian Hübscher, a geophysicist at the University of Hamburg. Raised to about 270 meters above sea level, they remain orderly and calm compared with the crumpled chaos of the Alps.

Over millions of years, wind and rain have sculpted them further. Streams carved gullies into their flanks. Open meanders wrapped around the hills, slowly rounding them, leaving behind closed loops etched into the desert. Yet even now, scientists admit, much is guesswork. Kazakhstan’s long history within the Soviet Union and its remote geography have left them little studied.

What is certain, however, is that their birth owes nothing to modern, human-driven climate change. That would be a third, entirely different way seas vanish: when people shut off the tap.

The Human Factor

The Caspian Sea, Earth’s largest inland body of water, still stretches 1,200 kilometers long and 435 kilometers wide. The mighty Volga River feeds much of it, bringing not only fresh water but also sediments from Russia’s snow-covered forests. Over geologic time, these deposits have formed horizontal layers of sandstone, clay, and limestone built from the remains of tiny marine organisms.

But in recent decades, humans have disrupted the cycle. Dams slow the Volga’s flow. Upstream, vast quantities of water are diverted for agriculture and industry. Sediment now clogs the delta instead of spreading into the Caspian.

Over a 200-kilometer front, the river has deposited sands that could fill Lake Constance five times over. The result is a vast delta of reeds and lotus fields – the largest reed beds and northernmost lotus fields on Earth. Beautiful as they appear, they are also ominous. The Caspian Sea is shrinking by human hands. In just three decades, its level has dropped by 1.3 meters, drying up an area the size of Belgium.

Could it Vanish Entirely?

What if the Caspian were to disappear, just like the Paleo-Tethys before it? Would new “Tiramisu Mountains” rise from its bed millions of years later?

Unlike the Aral Sea – which vanished in decades because it was shallow – the Caspian is divided into basins, one of which plunges a thousand meters deep. It would take far longer to vanish.

If it did, the seabed would be capped with a thick white crust of salt. Beneath it, sedimentary layers would begin to form – the foundations of a new geological tiramisu. Only through tectonic uplift and the polishing hand of erosion would colorful hills eventually emerge.

Perhaps, then, seas retreat so that mountains may be born. And perhaps, millions of years from now, striped hills will once again rise where waters once lay – reminders in stone of how endlessly dynamic, and endlessly beautiful, life on Earth truly is.

*All images included in this piece belong to Daniel Kordan.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.

2026 Photography Tours, Workshops and Expeditions

Daniel will be leading a variety of photography trips throughout 2026 to multiple Asian destinations including Indonesia, Vietnam, the UAE, Japan, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. Find out more and book your place here.