The Textile Obsessed Island of Sumba

David and Sue Richardson are independent UK-based specialists in Asian textiles

Just a 90-minute flight from the tourist-choked streets of southern Bali lies the fascinating and rarely visited island of Sumba, with its unique religion, its megalithic culture and its superb textiles.

In the past Sumba was divided into over thirty domains, each led by a noble family. There was strict social stratification between the aristocracy, the common people and the slaves, of which there were many. Until the early twentieth century, while the Dutch were still struggling to gain control, there was constant warfare between neighbouring domains. Warriors set out on raids to take enemy heads, which were then ‘beautified’ before being displayed on skull trees in the village centre.

Whilst most Sumbanese identify as Protestants, many still believe in the traditional marapu religion in which ancestors act as intermediaries between the living and a supreme deity. On Sumba, a person’s funeral remains the most important event in their life – the moment at which they join their ancestors in the afterlife. Huge resources were, and still are, invested in an elaborate three- or four-day ceremony, especially for the royal families. The bodies of the rajas (kings) and their wives are wrapped in up to one hundred textiles, and lie in state for many months if not years. They are finally buried in tombs topped with massive stone sarcophagi topped with upright penji carved with crocodiles, turtles, crayfish, roosters and other meaningful symbols.

While the creation of an independent democratic Indonesia led to the nobility being stripped of their political power, they still attract enormous respect. They also still own extensive tracts of land, large herds of livestock and many former slaves, who today are effectively unpaid indentured servants. Because the nobility has always benefited from huge reserves of labour, the noblewomen have always had ample free time to devote to the production of textiles. It is because of this strict social stratification that the coastal villages of East Sumba produce some of the finest warp ikat and the most complex supplementary warp textiles in the whole of Southeast Asia. Indeed, the whole region is obsessed with textiles. The exchange of textiles underlies every stage of a person’s life. Any problem can be resolved through the gift of textiles.

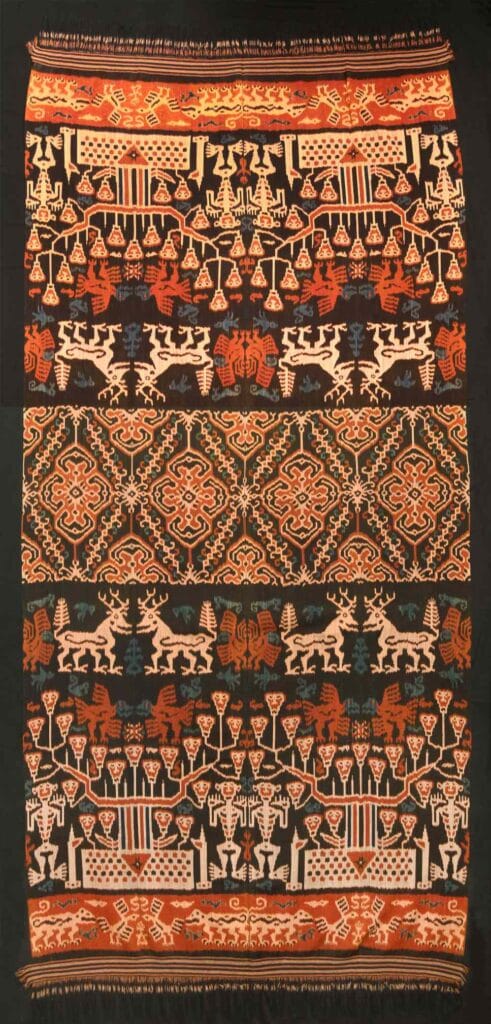

The most stunning East Sumba cloths are the men’s hip wrappers and shoulder cloths, known as hinggi. They were never made singly but usually as pairs, or in some cases as threes, fours, sixes or sometimes more. Each cloth was made from two loom lengths sewn together side to side. The hip wrapper was wrapped around the waist with the central section placed at the back. This is why the central section was always decorated with a geometric or abstract pattern. The shoulder cloth was worn over one or both shoulders.

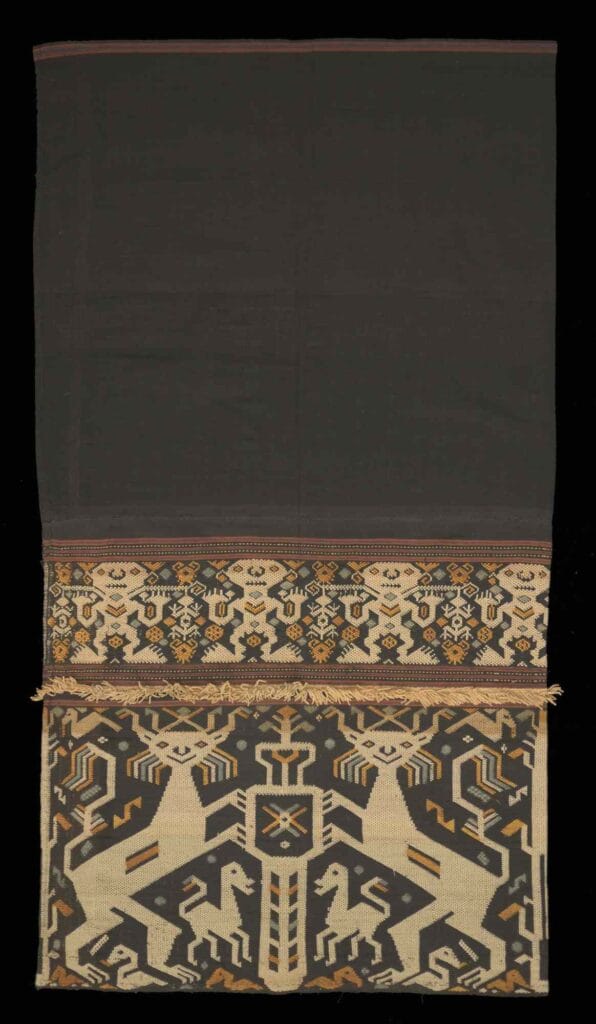

While men’s textiles exhibit an enormous variety of patterns and designs, the greatest diversity of textile types is found in women’s tube skirts, known as lau. These are made from two or three loom lengths of cloth, sewn selvedge to selvedge, and then formed into a tube with a rolled side seam. They are generally pulled tight around the waist with a fold and then the top is turned inwards to hold up the skirt.

Some women’s lau are decorated with warp ikat, the same technique used for men’s cloths. However, the most technically complex lau are those woven using the supplementary warp technique, known locally as pahikung. In these skirts the decoration is added by the use of supplementary warp threads that float above and below the ground weave in a way that creates a pre-designed pattern. To make pahikung, the loom has to be pre-programmed with the design, which is read from a pattern called a pahudu that records which supplementary warps float above the ground.

Some of the most elegant lau pahikung are woven on an undyed ground and are then sewn into a tube skirt prior to dyeing. The pahikung section is then wrapped inside the outer sheath of a frond from the Areca palm (a kuamba) and tightly bound so that it completely resists the dye. The whole skirt is then mud dyed, with the exception of the section of pahikung that has been protected from the dye.

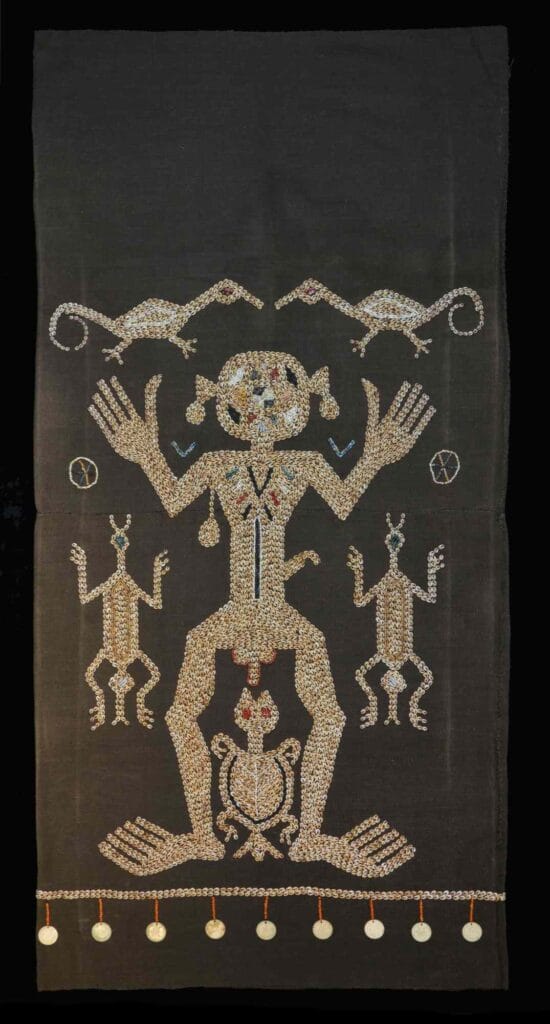

Another speciality of East Sumba are the lau wuti kau, which are embellished with small nassa seashells. The term wuti kau means cut shell, because the top of the shell is removed with a knife and an extra hole is then punched through the shell, so that it can be attached like a button. In the past lau wuti kau were exclusively restricted to the royal families. A noblewoman would gift a lau wuti kau to her daughter at the time of her marriage. It was placed in the dowry basket (mbuala ngadidi), along with all the girls valuables and textiles that she would take to her new family. She, in turn, would eventually pass them on to her daughters.

Many lau wuti kau are decorated with an anthropomorphic figure representing the founding ancestor or marapu of a clan. Such figures are generally tightly proscribed. They are mostly male, carry a bag for betel nut (sirih-pinang) over one shoulder and a parang on the waist. They generally stand face and hands forward with raised arms and fingers and splayed legs and feet. The round head is normally featureless apart from a roundel or cross, the one exception being the ears from which hang earrings. Sometimes the chest is shown displaying the ribs, like in an x-ray. The genitals dangle above a creature – normally a crayfish or crab with raised open claws, but occasionally a butterfly, insect, lizard or turtle. This combination of genitals and creature symbolises the cycle of birth and rebirth.

Interestingly, two Australian archaeologists working in cave sites on nearby Timor Island, just over a decade ago, recovered 91 nassa shells from layers ranging in age from 2,000 to 6,000 years ago. A detailed examination of these shells showed that they had all been processed and bore marks of having once been attached to some organic surface. It is impossible to say what this may have been since it had long since decayed. Yet it is clear that the decorative technique of shell appliqué has been in use in this region for many millennia. There are many other types of Sumbanese women’s lau, far too many to cover in this short piece.

Indonesia is a fast-developing country and in many neighbouring islands the traditions of textile manufacture are disappearing fast. Today young people have more choices and want to work as teachers, doctors and nurses or civil servants. However, Sumba is a very poor island and its passion for textiles means there is still a huge home market for hand-made cloth. Consequently, in many villages the production of textiles continues to provide employment for many women and men. The unique textile culture of Sumba is safe, at least for the next few decades.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.

More from this author:

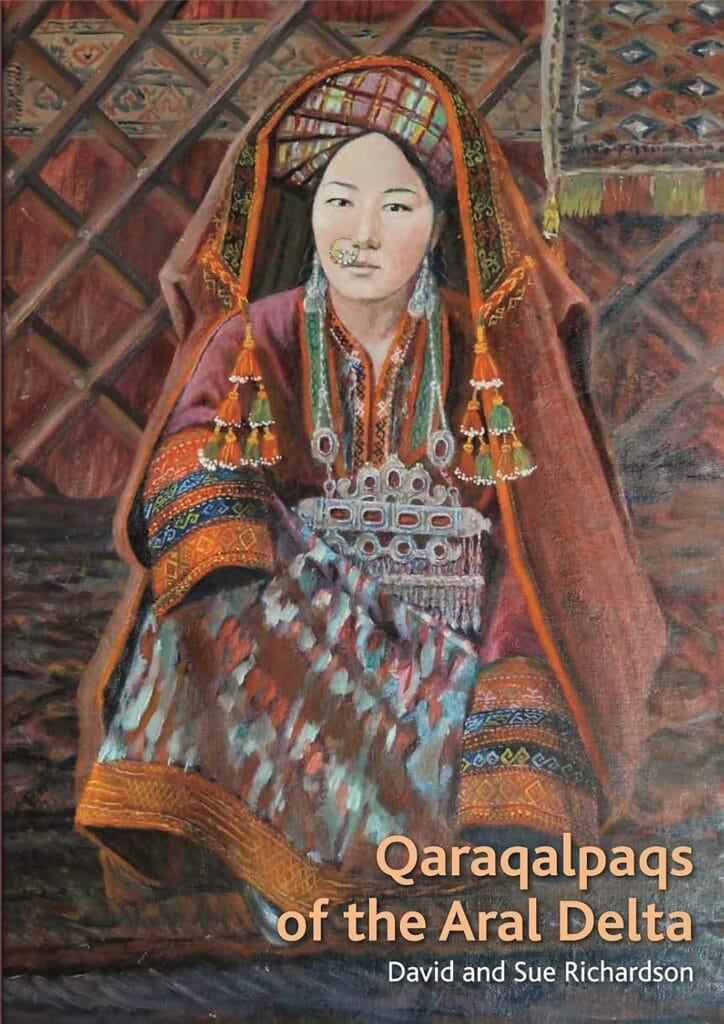

Qaraqalpaqs of the Aral Delta

This beautifully illustrated book introduces the textiles and weavings of the Qaraqalpaqs. It cuts through the myths that have surrounded them for over two centuries and explains who they are and where they come from. It explores the Qaraqalpaqs choice of fibres, natural dyes, and looms, and describes the textiles that they wove locally as well as those that they imported. It provides new insights into the local speciality craft of producing polished cotton alasha, and the little-known ikat weaving and silk sash weaving industries of Khiva. Qaraqalpaq headwear, costume, and jewellery, as well as their dwellings and furnishings are also covered.