The Literary Traditions of Brunei Darussalam

Kathrina Mohd Daud and Ampuan Brahim bin Ampuan Tengah

When Brunei Darussalam appears in global media, it is usually within the context of one of three points of emphasis: the perceived extravagance of the monarchy, the implementation of Shariah law in 2013, and dismissal as a somewhat unknown and perhaps exotic jungle island. It is not unusual for articles discussing Brunei to mention by way of introduction that little is known about the country.

In contrast, how do Bruneians speak of themselves, and their nation, culture and identity? Approaching the literary traditions of Brunei is one way of engaging this question. This article will offer a broad chronological overview of the literary traditions of Brunei from past to present, offering some observations on the material conditions of production as well as the evolving themes and forms of Bruneian literature.

Oral Literature

Prior to the arrival of a written tradition with Islam in the mid-fourteenth century, Brunei is believed to have enjoyed a rich oral tradition. Along with poetic forms such as syair and pantun, legends, folktales, riddles and mythology proliferated, although much of these have been lost to history. The earliest known form of oral literature in Brunei is the mantra, which speakers were able to adapt to the coming of Islam by incorporating elements of the new faith.

There has been strong interest and continuous efforts on the part of contemporary scholars of storytelling in Brunei, amongst them Maslin Jukim/Jukin, Frank Dhont and Janet Marles, to recover oral narratives. Such efforts have ranged from collecting folktales and legends to documenting the oral histories of survivors of the Pacific War (1941-1945).

One unique undertaking has been the video recording of performances of the ritualised poetic form of the diangdangan, a rhythmic oral literary form whose memorised verses are accompanied by the dombak, a percussion instrument. Thematically a quest narrative featuring a royal protagonist, specialised performers or pendiangdangan memorise specific stories for performance. There are no professional pendiangdangan remaining in Brunei today.

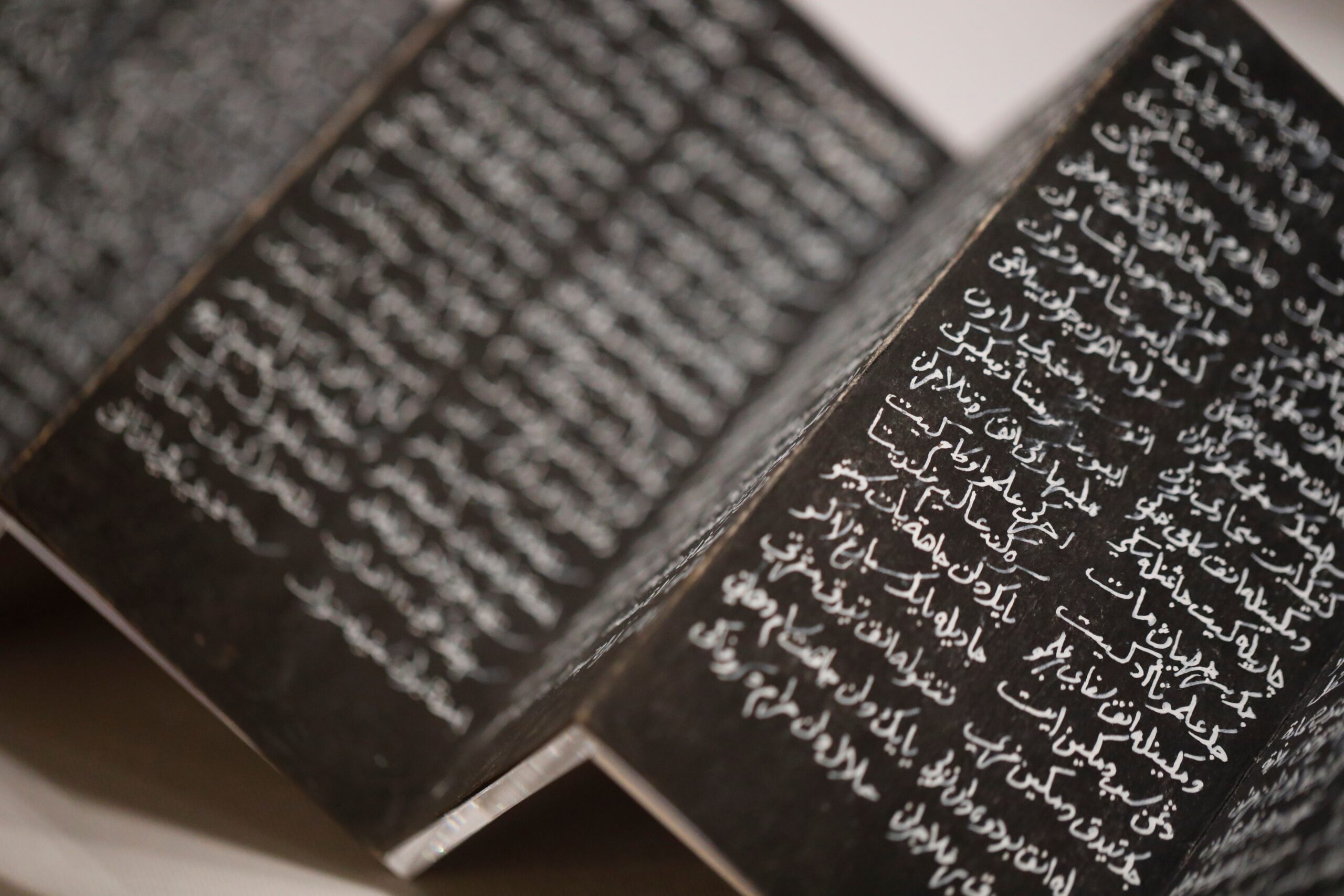

Traditional Bruneian Literature

Given the paucity of surviving material, scholars of Bruneian literature generally use the term to refer to any written text, manuscript or documentation. Thus the Hukum Kanun Brunei, a record of the legislation enforced during the 15th and 16th centuries, as well as the 1735 Salasilah Raja-raja Brunei (Genealogy of the Kings of Brunei) are referred to as traditional texts of Bruneian literature.

Attention to traditional Bruneian literature has focused as much or more on its historiographical value as much as its aesthetic qualities. The lines between literature and history, the mythic and the factual, have not always been distinct in Bruneian culture and literary scholarship.

Modern Malay Literature of Brunei

Modern Malay literature in Brunei begins with a royal advisory poem in 1847. Written by the nobleman Pg Shahbandar Pg Mohd Salleh in response to British territorial incursions into Brunei, most notably in the form of James Brooke being appointed Rajah of Sarawak, Syair Rakis, also known as the poems of petition, so impressed the monarch at the time that he decreed that copies should be made and distributed to all members of the court. Both critical and cautionary, the thirteen verses of the poem are sometimes perceived to correspond with the thirteen articles of the Anglo-Brunei Treaty of Friendship and Commerce of 1847, which amongst other items, formalised the cession of Labuan to the British.

Although written in traditional syair form, scholars have argued that Syair Rakis marks a departure from traditional Bruneian literature such as Syair Takbir, Syaing Rajang and Syair Awang Semaun, due to its critical outlook and transnational perspective.

Royal support and endorsement proved key to the continuing development of Bruneian literature. Yura Halim’s 1951 Mahkota Berdarah or “The Bloody Crown”, canonically the first Bruneian novel [1], a historical retelling of the 17th century civil war, was given the stamp of approval with a royal foreword from the then Sultan of Brunei.

The development of Bruneian literature has been characterised by long pauses punctuated by individual utterances. This characteristic is shared by other creative forms, including theatre, and was largely due to political circumstances within the country – the internal political upheaval of the 1960s effectively stifled burgeoning artistic production nationwide.

The next Bruneian novel was published in 1968, by Mohd Salleh Abd Latiff; he would then survive another 13 year literary silence to publish another novel in 1980. Novel writing and other creative production flourished in the 1980s, largely due to the support of government institutions, foremost of which was the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP) or National Language and Literature Bureau. Brunei’s declaration of independence in 1984 saw writers apply themselves to the question of imagining Bruneian nationhood and identity in the modern era, by addressing social issues as well as preserving snapshots of a quickly-changing society.

The nation-building project was one taken up by writers both in their professional and writing lives – today, amongst the veterans of the Bruneian literary landscape are the state Mufti of Brunei since 1994, Haji Awang Abdul Aziz bin Juned (pen name: Adi Rumi), and the Language Ambassador Ampuan Haji Brahim bin Ampuan Haji Tengah (pen names: Brahim Tengah and Rahimi A B). The DBP continues to be the primary publisher for Malay literature in Brunei.

The establishment of the national university, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, in 1985, saw scholars’ efforts to achieve recognition of Bruneian literature as part of Malay literary tradition. Early scholarship which included Bruneian literature in studies of Malay literature were Kesusasteraan Tradisional Melayu [Traditional Malay Literature] by Jamilah Ahmad dan Zalila Sharif (1993), Sebutir Pasir [A Grain of Sand] by Siti Hawa Haji Salleh (1992), and Kesusastraan Klasik Melayu Sepanjang Abad [Classical Malay Literature through the Ages] by Teuku Iskandar (1995).

In the present, the Malay literature programme at the university continues to have a strong relationship with the DBP as champions of local literature.

Contemporary Anglophone Literature of Brunei

Until the early 2000s, Bruneian literature was almost exclusively in Malay, and it is only recently that “Bruneian literature” has come to refer to works in English as well as Malay. The first Anglophone Bruneian novel was published in 2009, and since then the novel form has been the major medium for the production of Anglophone Bruneian literature, with over 20 novels having been published over approximately the last 15 years – there have been comparatively few poetry collections, creative non-fiction collections, and 2 script anthologies in English.

In the first ten years of Anglophone Bruneian literature, the majority of the novels were self-published and primarily available digitally, difficult and expensive to acquire within the country. Scholars have noted that these first articulations in English have positioned themselves primarily for international rather than local readership. In response to the growing production of Anglophone literature, a number of small independent publishers emerged, and from 2020 onwards, a shift towards local publishing can be observed, with a concurrent emphasis on print and therefore local over digital and international circulation.

Thematically Anglophone Bruneian novels have for the most part, avoided contemporary realism, turning instead to speculative imaginings of the nation, both in a surreal or fantastical present, as well as in imagined futures. There have also been a small number of historical reimaginings of the nation. This suggests a dual engagement with the preservation of history as well as an interest in the nation as she might become. Much like the Malay literature of Brunei, Anglophone literature is socially engaged, and curious about questions of nation.

Bruneian Literature Today

Today Bruneian literature can be said to have a cultural significance that belies the relatively small number of works that have been produced, with canonical texts included in the curriculum at the secondary and tertiary levels, and strong support from the relevant government agencies, and historically, from the monarch.

Over the last five years, the average number of literary texts produced in English and Malay per year has hovered around the 14-16 mark – this includes children’s picture books, poetry collections, as well as novellas and novels. Sales per title are on average also relatively low, approximately 100 units, although bestsellers can reach 800-2000 units.

The literary ecosystem remains active, although on a small scale. Spoken word events, book clubs, and writing groups are easily discoverable, and the annual Pesta Buku (Book Fair) helmed by the DBP enjoys a modest audience. Apart from literature, narrative making through mediums such as film and theatre continues on a similarly small scale, oriented generally but not exclusively, towards local audiences materially and thematically.

What does the future hold for Bruneian literature? Some hints lie, perhaps, in the popularity of historian Rozan Yunos’s essay and article collections of Bruneian history, legend, and folklore, as well as Aammton Alias’ bestselling Real Ghost Stories of Borneo series, now on its 8th volume.

These forms draw on local narratives, settings, atmospheres, suggesting that now more than ever, in an age of pervasive, sensationalist and over-simplifying global media, Bruneian writers and readers are looking inward, committed to telling their own stories and listening to their own storytellers.

[1] Literary scholar Syahwal Nizam (2020) makes a convincing case for the 1952 Tunangan Pemimpin Bangsa by H M Salleh as being the first Bruneian novel, but canonically, Mahkota Yang Berdarah is generally accepted as the first.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributors, not necessarily of the RSAA.