The Golden Melons of Samarkand

Anna Ansari is an Iranian-American cook and writer focusing on the intersection of food, family, and history

The following is an edited excerpt from Silk Roads – A Flavor Odyssey with Recipes from Baku to Beijing (DK, 2025).

It all started with a melon.

The melon in question was an attempted souvenir from a three-week, government-sponsored trip to the USSR my Iranian father, then a middle-aged American citizen who had been living in Michigan for nearly 15 years, and a group of 20 American doctors took in late 1978. Traveling across the Soviet Union, the physicians had been invited ostensibly to bear witness to and learn from the “great advances” being made in Soviet medicine. Spoiler alert: the Soviets didn’t achieve their objective on that front.

One day at a Tashkent market, my father recognised a melon similar to one he used to eat in Iran – specifically a variety from the eastern part of his native country, near the border with Turkmenistan. The hotel in Tashkent had served melon to the group of Americans, but it had been disappointingly bland and mealy – “not quality.” The market melons, on the other hand, were superlative.

My father brought a melon back and started carving it up in the hotel dining room. There is a smile in his voice as he recounts how “it was like a riot”: him, holding court at a drably covered table, cutting pieces of melon with surgical precision, doling out samples to his fellow physicians. “This is like heaven,” said one doctor, while another cried, “So sweet! So juicy! So good! Why haven’t we had anything like this here?”

Complaints were lodged to the tour leader and the hotel. Mealy melon no more! The Americans demanded quality fruit! And, so they were promised it … and so the Soviet hotel managers failed to follow through on their promises. And, so my father became the designated melon buyer, escorting fellow physicians to the market to procure “quality” fruit.

On his last day in Tashkent, he spotted “a real winner” of a melon, so beautiful and perfect that it needed to accompany my father back to the United States. His children, my older brother and sister, needed to taste this melon, this ultimate souvenir. “Ansari’s melon” thus joined the travelling party, rolling around overhead luggage racks from Tashkent to Moscow, Moscow to DC, its rolling announced by amused cries of, “Hey, do you heart it? It’s Ansari’s melon again! It’s on the move!” My father envisioned slicing open the juicy orb for his son and daughter, sharing this golden fruit of Samarkand; the US customs agent at Dulles Airport unfortunately had other plans.

“Did you bring anything from the Soviet Union?” asked the agent.

“No. Nothing,” my father replied, thinking he had it made. The agent didn’t even notice the melon…until my father volunteered, “Well, I just have this one melon.”

“Melon?! Let me see. No. No. You cannot bring this in.”

My dad begged. “Please. I have carried this all the way from Uzbekistan. I have brought it so far. It is for my children. Please.”

“No way. Absolutely not. You cannot bring that into the country.”

And, so the agent took the melon, deposited it into a trash can, and sent my father on his way, souvenir-less, melon-free, back to Detroit, back to his family and home, carrying with him only the memory of the most delectable fruit he had ever tasted.

For years, I have loved and been fascinated by The Golden Peaches of Samarkand, a 1963 treatise on the trade of material objects between Tang Dynasty China (618 – 907 CE) and Central Asian kingdoms, written by the late American historian Edward H Schafer. The book is divided into 18 categories, ranging from men to plants to textiles to pigments; jewels; books; and, of course, to foods. Supposedly yellow peaches “as large as goose eggs” made their way from the kingdom of Samarkand to the dynastic capital of Chang’An (modern-day Xian) on a diplomatic caravan, across treacherous deserts and mountain passes. Though Shafer, in his introduction, notes that the titular “golden peaches” might not have been peaches at all, for him, as for the people the Tang court, this fruit, whatever it may have been, represented something so prized and beloved by Samarkandians that it merited being carefully packed and guarded and shipped overland nearly 3,000 miles to the Tang capital as tribute.

This always reminded me of my father and his attempted import of the Uzbek melon – a fruit so singular that all he wanted was to bring it to his children. So that they could taste this golden melon of Samarkand, if you will, he hand-transported it across the world, a treasure, a tribute to my siblings.

There is actually a very easy way of taking Uzbek melons home, one that goes back centuries. One of the earliest written mentions of Uzbek melons comes from the 10th century Arab traveler, writer and geographer Muhammad Abu al-Qasim ibn Hawqal, who describes Khorezm melons as “ugly” but of the “highest sweetness.” He tells us the melons are cut up, dried and “sent for export to numerous places of the world.” In the 13th century, Marco Polo writes about them as well, noting that “they are preserved as follows: a melon is sliced… then these slices are rolled and dried in the sun, and finally they are sent for sale to other countries, where they are in great demand for they are as sweet as honey.”

Like ships stocked with citrus to ward off scurvy, camel caravans travelled across Central Asia laden with strips of dried melon, pregnant with sweetness, vitamins and the taste of home, comforting and nourishing their human members on their long journeys. Eventually, they also carried fresh fruit; by the mid-to-late 19th century, massive caravans of 1,000 to 2,000 camels transported ripe and ripening melons across Central and East Asia. Today, Uzbek melons still astonish. Harvested in early autumn, some are left to ripen for months in traditional sheds, growing ever sweeter as starches transform into sugars. They emerge in winter at ten times their original price, juicy with both sustenance and symbolism. On my first visit to Uzbekistan, I paid $45 for an elusive winter melon in early April, the most money I have ever spent on a fruit. Was it worth it? Taste-wise, maybe not. But I would gladly have shelled out even more cash for the opportunity to finally taste a fruit about which I had spent decades hearing.

Though my father’s Uzbek melon never reached my siblings in its physical form (an aside from my dad: “I bet that customs agent took it and ate it himself, that son-of-a-bitch”), my father did succeed in giving the dream of that melon to his children, including the ones yet to come. (Me! I’m talking about me!) He made it bigger than life. He made the melon the most magical, flavorful, beautiful fruit. He imbued it with a sense of wonder, longing, and joy – pure joy for what the land can give us; for what storytelling can give us; for what our heritage, memory and history can give us. He gave that to me, and I give it to you now, here: my imagined golden melon of Samarkand, an emblem of everything the Silk Roads have given and continue to give to us all.

We talk often today about where our food comes from. About carbon footprints and food miles. About localism and seasonality. But there’s another story too: the one that stretches back centuries, across deserts and mountains, across borders and languages. The story of how our foods really got here. The melon you slice on a summer afternoon carries with it centuries of trade, migration, and memory – whether you know it or not.

That’s what I try to capture in Silk Roads – A Flavor Odyssey with Recipes from Baku to Beijing: how ingredients like melons, rice, noodles, and spices travel; how they link families, histories, and empires; how they show up in the dishes we make today.

I can’t give you my father’s melon, but I can give you recipes that carry the same sense of wonder – dishes that have rolled through time and across borders, much like that melon did. I hope they inspire you to cook, to travel (even if only from your own kitchen), and to taste the world the way my father once wanted me to taste that melon: with joy, awe, and no small amount of humor.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.

Silk Roads – A Flavour Odyssey with Recipes from Baku to Beijing

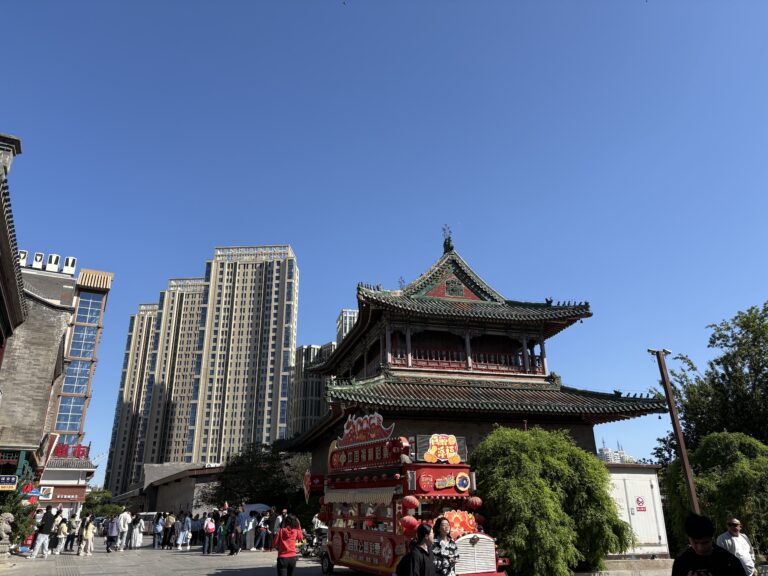

In this cookbook, Anna Ansari takes us on a culinary, historical, and personal odyssey across the Silk Roads. Weaving together essays, family photography and 90 recipes, Ansari brings life to the flavours of the Silk Roads – from the walnut groves of her father’s Iranian childhood, across Central Asian markets brimming with fragrant melons and thronged with fat-tailed sheep, and into the neighbourhoods of modern-day Chinese cities. Discover delectable dishes from Baku to Beijing – Azeri-Iranian stews served with crispy-bottomed rice, dill-infused noodles from Western Uzbekistan, Georgian cornbread, Uyghur lamb chops and all kinds of dumplings.