Pakistan – An Era Past

Most recently a Director of VanEck in New York, Tom Butcher has travelled extensively, particularly in South and Southeast Asia.

Fortunately, at a little after four in the morning during a severe thunderstorm, the sole policeman at an empty Zero Point in Islamabad flagged down one of the very few vehicles on the road and ordered the driver to take me to the airport. After three days waiting, I really did not want to miss my flight. And, a couple of hours later, I was aboard the Fokker Friendship as it flew by sight and below the mountain tops to Skardu.

Researching the requirements and realities of fly fishing in Northern Pakistan was a challenge. My visit to the Pakistan High Commission in London only seemed to support further the thinking amongst my friends that I was seriously deranged: my enquiries there were met with a blank stare. But there was, as always, the London Library. So, after many hours amongst shikaris, sporting tales and maps from nineteenth century Imperial India, I felt just a tiny bit more prepared: but only minimally.

Skardu

Turn right at Nanga Parbat (very close to the cockpit), fly down the Indus and you are at Skardu. Little more than a long, hot and dusty main street, but boasting both a “new” and an “old” bazaar and with spectacular views of the Indus from its fort, the town was small, dirty and unprepossessing. But, as with everywhere else in the north, police checks were plentiful, suspicion strong and registration a must.

Reached along a dusty, rutted track seven kilometres south of Skardu, Satpara Lake (2,636 meters) lay blue, deserted and totally unspoiled. The views and silence were spectacular. The Government Rest House (as with most places in which I stayed) lacked both running water and electricity. And, at night, the noise was only ever of the mice scurrying around on the stone foreshore and the plop of trout. I brought in my first lake fish (as with a number following it) on a Peter Ross and, as an indication of just how un-fished the place was, on the Hargassa Nullah I once caught a fish on my back cast.

The village of Satpara – at the far end of the lake where it is fed from the waters off the Plains of Deosai – was medieval looking. Early one morning, an old retainer came towards me carrying a stout staff, knapsack and wearing a very dirty shalwar Kameez. He was followed immediately by a woman, totally covered, on a mule, behind whom was a man in radiant red robes and bright white ammama. I stepped aside from the main path and they passed me without the least acknowledgement of my presence.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the contemporary world caught up with me soon enough: on the Siachen Glacier, India’s Operation Meghdoot was not far in the past and Pakistan’s response soon to come. On my last night at the lake, a very suave army colonel pitched up in his Jeep and questioned me in some detail about my travel plans in the north of the country. (Nearly as suave as the ex-Sandhurst Pakistani officer I met on one flight who described in detail his matched pair of Cogswell & Harrison shotguns (amongst other firearms) and then invited me to hunt Ibex.)

Hunza

Early one morning, leaving behind in the guest house a group of sixty or so exhausted Hajji making their way home by coach to Kashgar, I set off for the Hunza Valley. With stops on the way to buy grapes, for a boy to be sick, a flat tyre and to pick up other passengers who sat on the roof, I reached Passu in about five hours.

There may have been neither electricity nor running water and only two rooms at the Batura Inn, but why complain when the Financial Times in my room dated from only two and a half years prior? As did the TV Times.

Just recently opened to the public, the Karakoram Highway, or KKH (just a single lane of tarmac and this far north, save for the Hajji buses, used by few other vehicles) stretched into the distance toward China. Since I had had no luck trying to secure a visa to enter China via the Khunjerab Pass, I had to content myself with scrambling across the Batura Glacier and hitting the KKH 100 yards or so past the checkpoint (a tarpaulin-covered stone hut) and white-painted rock announcing “FOREIGNERS ARE NOT ALLOWED BEYOND THIS POINT.”

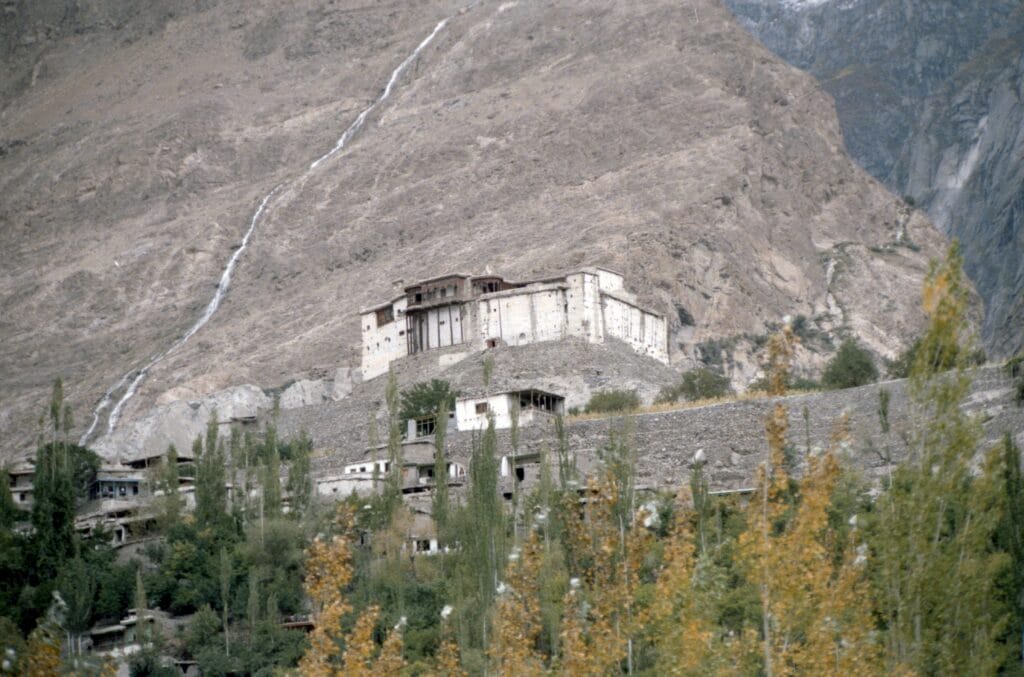

The view of the Karakoram (particularly Rakaposhi) from Baltit Fort was spectacular. To provide a little context, writing of the trip he took to the Pamirs in the autumn of 1894, Curzon said: “ … the little state of Hunza alone is said to contain more peaks of over 20,000 feet than there are over 10,000 feet in the entire Alps.” The fort itself, however, was falling to pieces, with glass panes falling from the windows and plaster from the walls and ceilings. Perhaps the most astonishing thing was to find a rotting shotgun case in one of the cupboards, together with a load of mouldy leather cartridge cases. Considerably smaller, Altit Fort, just down the road, was not in that much better shape. But atop the tower sat what appeared to be a plaster ibex – much like that on the insignia of the Gilgit Scouts or, now, the Northern Light Infantry (“NLI”).

The Gilgit River

Then little more than a dusty, rutted track, the road between Gilgit and Chitral measures some 358 kilometres, with around 155 kilometres of it aside the Gilgit River. I got to know it well.

Armed with “Trout in the Northern Areas”, given me by its charming author, Samiullah Khan, Assistant Director Fisheries Northern Areas in Gilgit, I spent a number of days fishing various stretches of the Gilgit River west of Gilgit. Particularly pleasant spots were Gahkuch, Gupis, the confluence of the Yasin and Gilgit Rivers and Khalti lake. At that time of year, September, the landscape was stunning. The road made its way through little narrow sunken lanes within the villages. Immediately outside the villages, the vines, mulberry trees and fields of maize were a vibrant green. Between the villages there was usually just barren rock and dust. The hills and mountains on either side rose with the trees high up, with peaks occasionally already snow covered.

Although there were brown trout in the river, my catch was normally confined either to the indigenous snow trout or to rainbow trout – all taken on the fly. (The introduction of brown trout is dated variously as either 1908 or 1916, with rainbow trout being introduced later.) Fishing on the Gilgit – wide, very cold and fast running – could not have been more different from that around Skardu. And, perhaps, not as fun. It certainly required heavier tackle and considerably longer casts.

Chitral

I had always been intrigued by the Siege of Chitral in 1895 and Colonel James Graves Kelly’s winter slog that March and April in deep snow from Gilgit over the Shandur Pass to relieve its fort. Having already travelled some 117 kilometres east toward Chitral, I decided to have a go doing the whole route in reverse, i.e. from Chitral to Gilgit, albeit neither in the snow nor dragging any mountain guns.

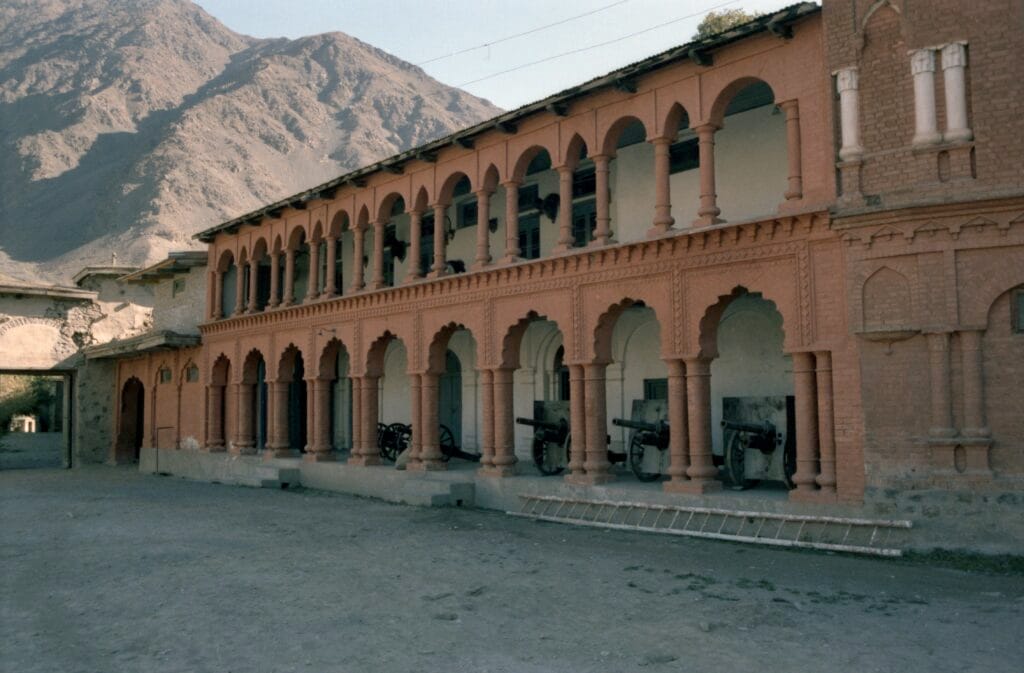

Still small and somewhat sleepy, Chitral had recently suffered a severe earthquake: on 29 July the previous year, a 6.6 magnitude earthquake had hit the Hindu Kush. In addition to killing eight and injuring 38, it caused landslides and considerable damage in both Chitral and Swat. This was much in evidence at the Tirich Mir View Hotel (my lodging when not staying with friends), where the dining room had totally fallen in. And, although still mostly standing, the fort, too, had been badly damaged. Some rooms consisted solely of a wall with a fireplace. Only traces of the original ornate plasterwork remained in others. However, an arched red façade with guns and trophy heads remained intact.

En Route to Gilgit

As always, I had to secure permission to travel back overland to Gilgit. Fortunately, it was given with no time constraints: the journey took five days – by Jeep and on foot.

The initial leg of the journey – nearly eight hours by Jeep from Chitral to Harchin – was exciting. Not only were the sacks of powdered milk on the back of the Jeep overloaded to the left (making clockwise bends precarious), but also, being “back heavy”, whenever we engaged four-wheel drive, the “conductor” had to come scurrying down from his perch atop the cargo, over the cab, over the bonnet and, facing us, jump up and down on the bumper to bring the front of the vehicle down, thereby preventing it rotating backwards over its back axle.

After a somewhat cold night on the floor of a grain godown, I walked early the next morning to the village of Sor Laspur (some 11 kilometres away and, then, tiny with no accommodation). And there I remained for two days until the next Jeep (with space) going east appeared. (As I learned a couple of days later, this being fighting “season”, many of the Jeeps that plied the Gilgit road had been “requisitioned” for the campaign over on the Siachen Glacier.)

Three-point turns in an overloaded Jeep on steep, high escarpments in bad weather aside, at that time of year the stretch between Sor Laspur, over the Shandur Pass, via Teru to Phandar was not that interesting. Shandur Top was desolate and cold, only about 50 feet below the snow line and Shandur Lake just looked putrid. The huge eagles wheeling above the dusty track as it made its way through the brown grass and scrub and the absolute quiet were, however, wonderful.

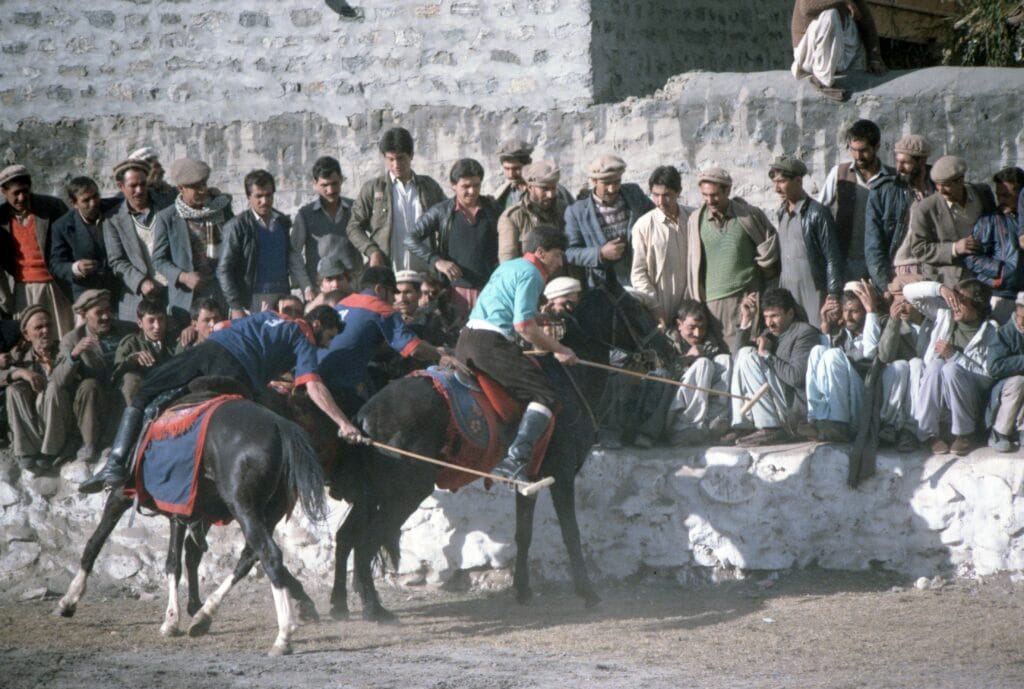

Whilst the annual polo matches between Gilgit/Baltistan and Chitral had been played at Shandur since 1930, it was only after 1986 (when they became “official”) that they “took off” and started to become what they have now become, a major tourist attraction. As I passed by the lake then, there was nothing there to indicate it was the venue of any such sporting event.

The 14 kilometres from Phandar to Pingal may have been dry and desolate, but it was incredibly easy on the feet. Although I had read about it often, I had never actually walked through real dust. In some places on the track, it must have been at least six inches deep and billowed up in huge clouds behind me with every step.

The last stretch that I had not before travelled, between Pingal and Gupis, turned out to be quite the most stunning of any of the previous legs, with the road perched many hundreds of feet above the seething Gilgit River. Once again, the Jeep was overloaded: in the cab, driver and three children and in the back, seven adults, two further children, four chickens and luggage. Despite running out of petrol, though, we made it back to Gilgit.

Coda

Fortunately, I arrived back in time to catch the opening day of the polo festival: bagpipes, marching bands, tugs of war, sword dancing, tent pegging, archery and balloon shooting (with shotguns) both when mounted and, of course, polo. NLI “B” routed the Shaheens nine to one in the first match.

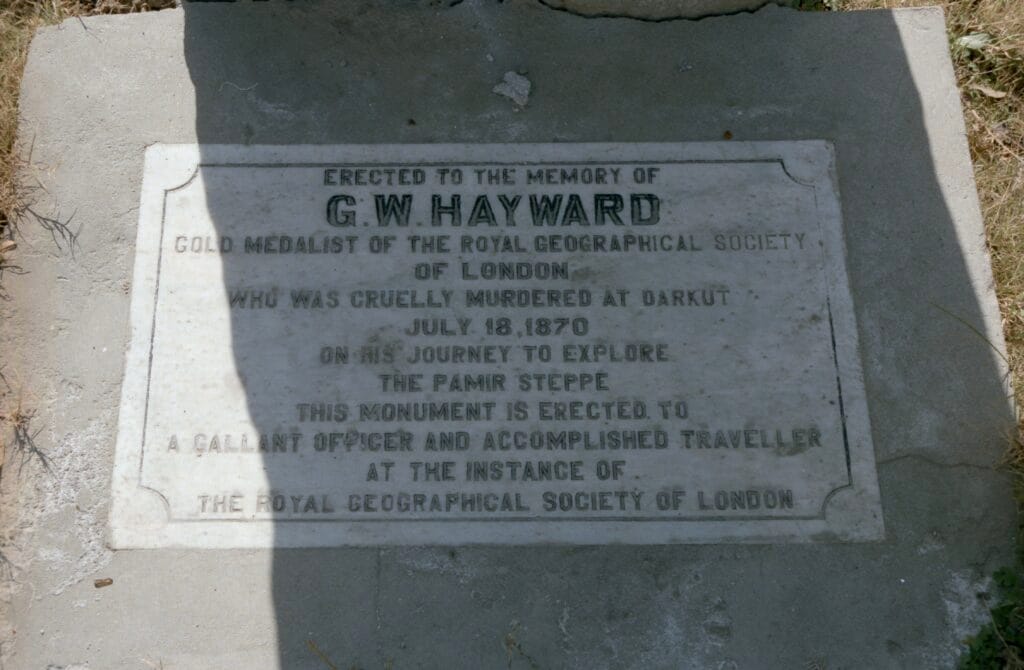

Finally, I was successful in accessing the British cemetery. And, on one of my last days in Gilgit, I was able to pay my respects, at his gravestone, to George Hayward, one of my heroes. Murdered on 18 July, 1870 in Darkut (in the Yasin Valley just north of Gupis), Hayward remains to me unmatched in both the breadth of his exploration and the number of his expeditions in that part of erstwhile Imperial India. As I looked down on his tomb, I offered my meagre travels and experiences to his memory.

*the title image shows the Karakoram Highway, Passu.

© 2025 Tom Butcher

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.