How to build a city, fast: life in one of China’s ‘new areas’

Sean Paterson is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society living in Guangzhou

Many of us in the UK are familiar with the trope of a old man taking his grandson for a walk and saying, ‘all this was fields when I was a boy’. In many parts of China, it could do with a bit of an update: all of this was fields last year.

News of China’s four-decade building spree filters back sporadically, from garbled accounts of ‘ghost cities’ to the travails of mega-developers like Evergrande and Country Garden. On the more positive side of the ledger, we sometimes see videos of truly astonishing bridges, railways, and tunnels, or of road junctions and hospitals built in days. Whatever one thinks of the causes and consequences, one thing is certain: China builds.

Over a decade ago, Bill Gates attracted social media attention by sharing Vaclav Smil’s calculation that China had used more concrete in just three years than the US had used throughout the entire twentieth century (6.6. gigatons between 2011 and 2013 versus 4.5 gigatons between 1901 and 2000, for those keeping track). As unbelievable as this may seem, just a few days anywhere in urban China will confirm it. Any randomly selected view from a balcony or office window will reveal a sprawling world of apartment blocks, mega-highways, and high-speed rail lines. Cities are the size of counties elsewhere in the world: Guangzhou, where I live, is about the same size as Yorkshire.

For anyone embarrassed by the UK’s sorry series of failed infrastructure projects – from the Lower Thames Crossing, to Heathrow’s third runway, to HS2 – the Chinese achievement is nothing short of remarkable. In the eighteen years that eight successive British governments have played around with HS2 – in its latest form, a hundred-mile railway from not-quite-Birmingham to not-quite-London – China has introduced, built and arguably perfected the world’s largest high-speed rail network, now 30,000 miles long and still growing.

In the few short years I have lived in China, I have taken brand-new, fully-electric trains through the eastern Himalayas to the kind of small towns where yaks still roam the streets, and hit 350kph in the once-remote Hexi Corridor, where Sven Hedin and Peter Fleming had to make do with Bactrian camels, and Paul Theroux jolted along on steam trains to nowhere. Overnight sleepers have carried me from Guangzhou to Beijing, first class, for half of what the LNER would charge me to go to Edinburgh. Recent innovations mean that any foreigner can book a train ticket anywhere in China, from their phone, in the language of their choice, for reasonable prices – no more travel agents, dodgy third-party websites or booking-office squabbles.

But it is not only the high-speed rail that impresses. The best places to get an idea of modern China – from the flair for infrastructure to the efficient bureaucracy – is in one of the country’s ‘new areas’, such as the one I live in.

* * *

If Guangzhou is shaped like a fish-hook curved around the northern end of the Pearl River Delta – the biggest, densest urban area in the world, home to more people than all of the UK – then Nansha is the tail end. Although long considered part of the city for urban-planning purposes, it does not always feel like it: it’s an hour in a taxi, or an hour and a half on the metro, to get anywhere near the glittering skyscrapers of downtown Guangzhou. Shenzhen, the neighbouring megacity to the south famously conjured up out of nothing in the 1980s and 1990s, is much closer; while Foshan, usually described as a southern suburb of Guangzhou, is firmly to the north.

Nansha pops up now and again in Chinese history. The Qianglong Emperor sponsored a temple to a sea-goddess A-Ma here around the time that he met the ill-fated Macartney Embassy in 1797, and much of the First Opium War was fought in the coastal creeks and swamps between here and Dongguan, on the eastern bank of the Pearl River. However, it was never really at the heart of things: Shamian, the island where foreign merchants were kept under the old Canton system, is a good forty miles upriver, as are the historic dockyards and fortresses of Changzhou.

Originally an obscure agricultural district – it still produces a lot of fish and vegetables – Nansha was chosen as a ‘new area’ as part of China’s ongoing ‘reform and opening up’ movement. Work began twenty years ago. The city’s metro network was extended south, raised up on a causeway across a patchwork of rivers and ponds, and connected to the city’s passenger port. An extra stop on the Hong Kong – Guangzhou express train was put in. Two enormous new suspension bridges were raised across the Pearl River, cutting travel time to the factories of Dongguan in half. Rural roads became ten-lane highways, and the latest electric vehicles and self-driving cars have replaced jerry-rigged jalopies and spluttering diesel trucks. New high-end apartment complexes and shopping malls have followed the infrastructure south, and attracted both retirees, workers and young families. Nansha fairly swarms with young children, one of the surest indicators that here is a place people feel confident about. All of this has been done at a speed and for a price that would make British eyes water. And, really, those houses and that mall weren’t there last year.

But what is a ‘new area’? Inspired by the successes of the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) first carved out in the late 1980s, as China first experimented with free market reforms, ‘new areas’ are designated areas of established cities designed to be as friendly as possible to business, free trade and the import / export sector. The idea is that if the government provides the infrastructure and some extremely favourable tax breaks, then business – foreign and domestic – will flock into the new areas, taking pressure off other parts of cities and spreading the benefits of development more evenly. In Nansha, no expense or effort is spared to make life in the ‘new area’ as convenient as possible for the Chinese exporter, the international businessman, or the ‘foreign expert’ (the catch-all term for everyone hired in to provide a specific service, from maritime engineers to schoolteachers). Road signage and important paperwork is bilingual, and the local government are hyper-efficient. Taxes and social security can be tracked and paid on a mobile app, and banks are more familiar with the tricky business of sending cash overseas than elsewhere.

Nansha is not the only ‘new area’ – they are scattered across China, from Lanzhou in the distant northwest to Pudong, now the beating heart of Shanghai. The most ambitious, Xiong’an, south of Beijing, aims to do much of what the capital currently does by 2050. It’s important to remember that the ‘new areas’ are designed and run on a much longer time-scale than we are familiar with in the West. Pudong, originally an unpromising marsh and the very first ‘new area’, was long written off by foreign observers, who now find themselves renting offices and apartments there. Even Shenzhen was once thought of by travel writers as an Ozymandian extravagance. So, while parts of the ‘new areas’ may look a little rough around the edges, or suggest overcapacity, only time will tell. For Britain, they suggest a different way of doing things – of building first and asking questions later – and a potential way out of the economic doldrums. As curious as they can seem, the ‘new areas’ shouldn’t be ignored. They have lots to teach us.

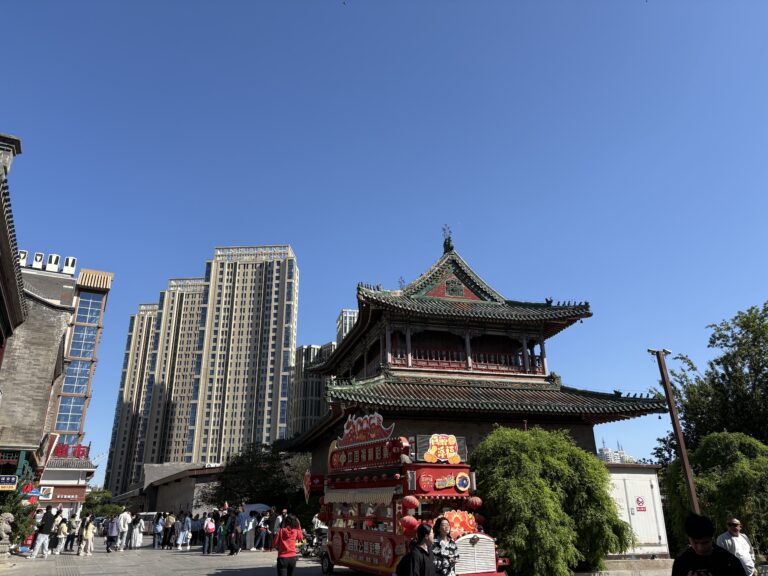

*the title image shows Nansha, Guangzhou: most of these buildings are less than five years old.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.