China’s road to Central Asia: the re-development of the Hexi Corridor

Sean Paterson is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society living in Guangzhou

Hong Kong is often referred to as ‘the gate to China’, and even today, it’s common to hear the broader Pearl River Delta megalopolis referred to in similar terms. Some might say the same of Shanghai. However, those who focus on the coastal approaches to China overlook a historically crucial northern passageway: the Hexi Corridor, once the final leg of the Silk Road, and today shaping up to become an essential part of the new Belt and Road.

The Hexi Corridor is the slender swan-neck on maps that links the northern and southern halves of Gansu, one of China’s hardscrabble northwestern provinces. Running straight between the outer reaches of the still-fearsome Gobi desert and the first ramparts of the Tibetan Plateau, it is a geological quirk: a narrow, nearly straight line of flat land, dotted with regular oases, almost tailor-made for travellers and trade.

For thousands of years, the Hexi Corridor has been China’s road to the west, a narrow funnel for travel between Xinjiang and the heartland cities of the Yangtze and Yellow River basins. Facing decades of fighting against the nomadic Xiongnu more than two millennia ago, the imperial authorities reared war-horses here. Marco Polo came this way in the thirteenth century, leaving descriptions of a chain of rich oasis towns. One town, that he called Campion (today’s Zhangye), took his fancy so much that he and his uncles tarried there a whole year on business during their journey to see the Great Khan.

Much later, even after the nomads had been beaten and the frontier pushed back again, the Hexi Corridor still kept some of its far-flung glamour for foreign travellers, as an authentically back-of-beyond place. It is here that much of Peter Fleming’s excellent travelogue News from Tartary (1936) is set. Later travellers also made it a set-piece of China travelogues: in the 1980s, Paul Theroux would rue his days on ‘the Iron Rooster’, a clanking steam train destined for the back of beyond; while a young William Dalrymple found his way around on the backs of cargo trucks, bound for Xanadu. Since then, Colin Thubron and Peter Hessler have both been repeatedly, and their accounts are the highlights of their books.

However, today it doesn’t feel nearly half as remote as it might once have been: you can get a decent latte in Dunhuang these days, and veteran travellers would surely say the effort and the mystery are long gone. I, for one, got as far as the northern edge of Gansu with a roller suitcase and extremely patchy Chinese. (Friends have gotten further, but the slow train to Kashgar will have to wait).

In the last twenty years, the Hexi Corridor has, with the rest of China, been lifted up out of absolute poverty, and is increasingly plugged in to the rest of the country’s infrastructure and economic networks. But make no mistake: Gansu is still a tough place, especially in winter. In February, when I was last there, temperatures get as low as minus 20 degrees centigrade, and rarely if ever make it above freezing. Thick coats and big hats are very much the order of the day.

Gansu’s soil is mostly dusty loess, and the growing season is limited. But it has long since moved on from agriculture: despite its remote location, it is a heavily industrialised area. In Jiayuguan, a factory town halfway up the Hexi Corridor where the Great Wall either ends – or, depending on your point of view, begins – the views take in dozens of belching smokestacks. Carrying on north on the new high-speed train, you pass steel-mill after steel-mill, often located hundreds of kilometres from anywhere else. This is, it turns out, a deliberate decision: the plants were moved out into the desert wholesale to improve air quality in the cities. The effects of the move are indisputable. In Lanzhou, once infamous as the most polluted city in China, February now brings crisp, freezing air and bright blue skies. Where Lanzhou leads, Jiayuguan will follow: already, the town’s first blast furnace is a (rather good) museum, and air pollution has fallen steadily.

But it’s not all steel mills and coal mines: the same train ride now takes one through enormous wind-farms that take twenty minutes to pass through even at top speed, making the best of the harsh desert winds that scour the region. The Hexi Corridor is to China what the North Sea is to Britain, or the Great Plains are to the US – an immense reservoir of wind energy. However, while Britain dilly-dallies about renewables – I was in primary school when the debate over offshore versus onshore wind-farms began – and the US flip-flops on fracking, depending on who is in charge, China has quietly built up the world’s largest turbine network. Gansu is now mostly wind-powered, a remarkable achievement.

The landscape all through the Corridor is laced with electricity pylons and phone lines, and the modern traveller will never once have to contend with anything less than 5G internet. Even where the roads run out, the wires never do. But this is no place to be buried in your phone: the views from the train windows are outstanding, and the slices of life one sees rushing past often quite amusing. (I still wonder, months later, what exactly was happening when I saw a small dump truck being carried in the bed of a much larger dump truck, both bumping along through the desert a very long way from the nearest road).

At the northern end of the Hexi Corridor, the old Silk Road split at the monastery-town of Dunhuang. From here, the southern route would skirt the bottom of the Taklamakan Desert, threading its way from oasis to oasis, with a sub-branch heading down towards the high passes of the Karakoram and on to Pakistan; while the northern route would hug the base of the impossibly-romantic-sounding Mountains of Heaven before both met again at Kashgar and passed on into Central Asia.

Today, the Hexi Corridor is coming back into view. Although industry remains important – Gansu’s factories turn out a decent chunk of the global steel supply, and the province’s mines provide enormous quantities of rare earths – services have represented the majority of the local economy for the last twelve years, and the share is continuing to grow. Two predominate: trade and tourism.

The tourist infrastructure in the Hexi Corridor is well-developed. Although everything is primarily aimed at domestic visitors, I blundered my way in with no major obstacles, beyond a constant mild bemusement from clerks, guards and drivers that a lone foreigner would make his way up here in the bitingly cold off-season, without a tour group. In the peak tourist season, after the spring rains have brought a little colour to the towns, but before the blistering 40C heat of high summer kicks in, the Corridor draws in more and more tourists. Many head for Jiayuguan and the first pass of the Great Wall; others for Dunhuang, to see its vanishing treasure-trove of Buddhist cave art. Many take in the ‘Rainbow Mountains’ of Zhangye, a geologist’s playground, or pay guides to take them to the smaller, less-well-known fortress ruins and cave-grottoes, if they find Dunhuang and Jiayuguan too busy. Although strictly seasonal, the tourist trade is a real boon to Gansu, as China’s immense middle class discover a taste for the faraway parts of their country.

Finally, the Hexi Corridor is returning to its roots as a trade route, as the ancient Silk Road is resurrected as the Belt and Road. The highways have carried truck-loads of Chinese goods to Kazakhstan and beyond for decades now, but are now joined by cargo trains, running on a dedicated parallel track next to the high-speed line. Most of the China-Europe trains, now running for nearly fifteen years, come through the Hexi Corridor. Although they can’t yet compete with the vast capacity of a Suezmax container ship, the trains carry an increasing share of China’s foreign trade, especially as China’s light industry moves from the old coastal cities and towards the heartland, particularly around Chongqing. As the patterns of global trade shift and shudder, the Hexi Corridor provides China with a valuable back-up route, and an easy path to the emerging markets of Central Asia. Before long, it may be spoken of in the same breath as the great port cities of the Pearl River and Yangtze deltas – as it once was, in the days of Marco Polo.

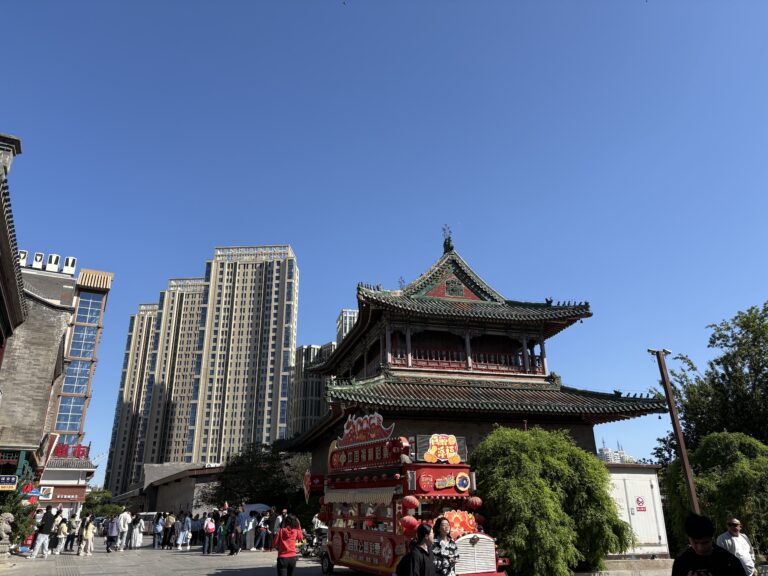

*title image – Looking onto the edges of the Gobi Desert near Dunhuang.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.