Burma: An Era Past

Most recently a Director of VanEck in New York, Tom Butcher has travelled extensively, particularly in South and Southeast Asia.

Pagan was a logical and important waystation as I made my journey from South Asia through to Southeast Asia, fishing and looking at temples.

I had kicked off my minor exploration of Buddhism in Pakistan, spending time exploring the likes of the Butkara and Shingardar Stupas in the Swat Valley and accompanying my friend Wladimir Zwalf in Taxila and Lahore – Wladimir was then engaged in researching his magnum opus A Catalogue of Gandharan Sculpture in the British Museum, which was published finally in 1996.

I ended my stay in India in Sikkim, in sight of Kanchenjunga. (Perhaps fitting, since I had started my travels in the shadow of K2.) As a schoolboy, I had been introduced to Buddhism by Fra’ Andrew Bertie, one of my teachers. An event that took place on my final day on the sub-continent was, perhaps, a fitting end to my time there. Visiting the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, a couple of miles outside Gangtok, I made it a point to meet with Nirmal Sinha, the institute’s founder and its director. By then in his mid-seventies, I mentioned Andrew to him and asked if he knew of him. His reply was: “Ah yes, Andrew! We last saw him in 1963.”

To Burma

Back then, in April 1986, visiting as a mere tourist, I was able only to stay in Burma for a maximum of seven days: no exceptions. So, rather than doing the typical tourist circuit of Rangoon-Mandalay-Pagan-Rangoon. I decided to focus my attention on Pagan.

It’s worth nothing that, like many countries in both South Asia and Southeast Asia at the time, Burma had strict capital controls. Not least, the import and export of Kyat were prohibited. Officially at least, all foreign currency exchange transactions needed both to be reported and made at the official rate (then around 7.6 kyat to the US dollar).

The best way of circumventing this iniquitous official exchange rate (and helping to ensure a visit to the country was more affordable) was the whisky and cigarette “solution”. It was so simple: purchase a bottle of whisky (preferably Johnny Walker Red Label) and a carton of cigarettes (preferably State Express 555) from duty free before boarding for Rangoon and sell them on arrival in Burma. (I got 400 kyat for mine.) We tourists could only assume these sales were, first, officially condoned and, second, an off-the-books source of revenue either for the government or individual government officials (i). Various other goods could also be sold quite advantageously for informal market kyat.

To Pagan

For those with money, and no fear, flying to Pagan would have been an obvious choice. However, expense aside, having experienced five fatal crashes in the ‘70s and three already in the ‘80s, for once I didn’t fancy the prospect of flying Burma Airways.

Although, by then, I had travelled many thousands of miles by train in South Asia over the previous months, the journey from Rangoon to Thazi (whence transport departed to Pagan) had to rate as the worst. Heat, crowds, smell, dirt, speed and discomfort aside, the subsequent hosting of flees was not something for which I had bargained.

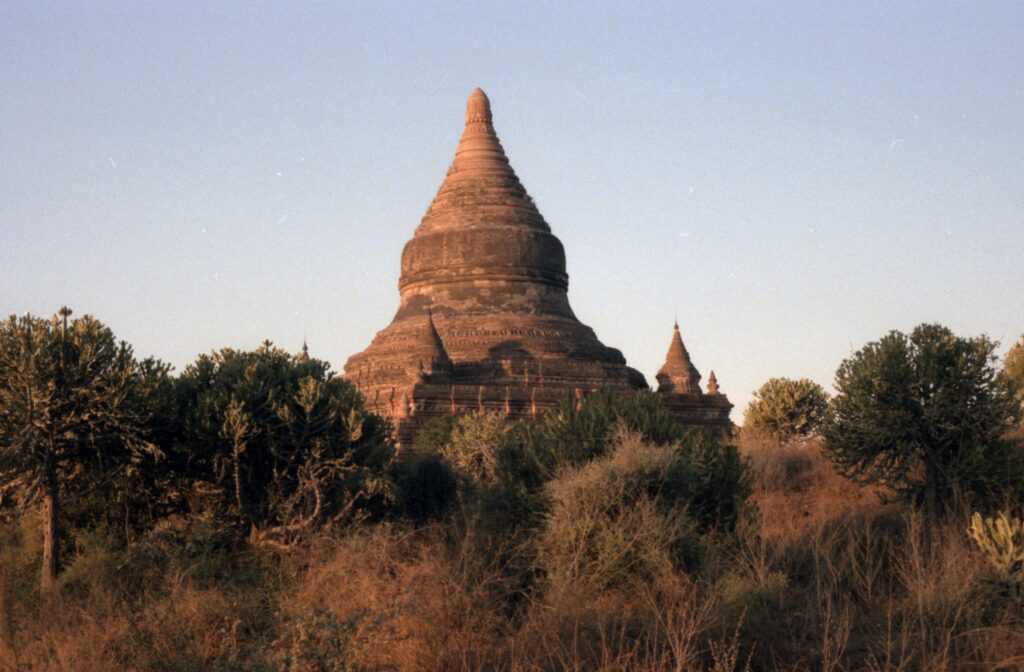

Now known as Bagan, Pagan is an archaeological area covering some 40 square miles extending back from the river Irrawaddy in central Burma. The whole area is covered in pagodas, temples and monasteries. The village of Pagan (consisting, essentially, of a single, dusty main street) was, then, just one of several small villages stretching downriver from the town of Nyang-U to the north, through Pagan itself and to Myinkaba and Thiriyapyitsaya to the south. But it was the one in which most visitors stayed and had some decent small, local restaurants, shops and lodgings.

Very sadly, though, the village of Pagan is no more. In 1990, not long after the 8888 Uprising (the main events of which took place on 8th August, 1988) and at the beginning of the SLORC dictatorship, one morning, without any prior warning, the villagers were forcefully relocated at gunpoint (ii).

By 1986, the country was already in a ruinous economic state and corruption rampant. It was quite obvious that the “Burmese Way to Socialism” (announced at the end of April 1962 by Ne Win’s Union Revolutionary Council) and the official policy of the Burma Socialist Programme Party, the country’s sole legal political party, was a failure. Instead of much-needed economic development, it had brought hardship, drug and border wars, a thriving and well-developed black market, ethnic strife and armed insurrections.

As a centre of international tourism in the country, not only was English quite widely spoken in Pagan, but the local community was not ignorant both as to what was happening outside Burma and, needless to say, the parlous state in which the country found itself.

In this context, two particular conversations have stayed with me. The first was about Burmese passports. They were, at that time I was told, impossible to get officially. And even if you could, it would cost you 2,500 kyat. However, you could, maybe, find one on the black market. It would set you back around 30,000 kyat.

The second chat was one I had with a young student, officially resident in Mandalay. He identified himself as the only Christian (a Roman Catholic) in Pagan. (At that time, not only were there restrictions on non-Buddhist religious activities, but those espousing religions other than Buddhism could face both social pressures and discrimination.) This young man was, he said, writing an “underground” guide to Burma avoiding the ubiquitous Tourist Burma. As a student, but a resident of Mandalay, he had to get permission from the police to stay in Pagan, which had to be renewed every week. (Any attempt to visit areas outside that in which you were resident appeared fraught with difficulties, not least because of the permits you needed.)

Pagan: Stupas and Temples

Over two thousand (at the time, 2,217 (iii) to be precise) Buddhist monuments (both stupas and temples) (iv) lie spread over the dusty, dry plain of Pagan. And, whilst Pagan’s origins date back to the mid-9th century, it was only in the 11th century, under its first ruler Anawrahta (1044-1077), that the really serious construction of temples began. And continued under the next great ruler, Kyanzittha (1084-1130).

As the story is told in The Glass Palace chronicle of the kings of Burma: “… Anawrahta, moved by religious zeal and under the influence of one Mon Theravada monk, Shin Arahan, requested a set of the Tipitaka, the Theravada Buddhist scriptures, from the Mon king, Manuha of Thaton. He refused and therefore [Anawrahta] seized the scriptures by military force and brought them to Pagan together with the captive king, Manuha, and his court, not to mention artists and artisans” (v). Once back home, Anawrahta, both sought to promote Theravada Buddhism and started building temples with a vengeance.

Paul Strachan, in his excellent book Pagan – Art and Architecture of Old Pagan, helpfully categorises temple building in Pagan as falling into three periods: the Early Period (c. 850-1120); the Middle Period (1120-1170) – predominantly during the rule of Sithu I (1113-1170) – architecturally, an experimental and transitional period; and, finally, the Late Period (1170-1300) – also a time of architectural experimentation, but, in addition, one of innovation.

Why so many fewer new monuments after 1300? It seems likely that, rather than there having been one specific catastrophic event, for example, a sacking, by the 14th century, no longer either a “hub”, or “political nerve centre” (vi), Pagan simply went into an economic decline. (It remains open to debate as to whether Pagan actually “fell” to the Mongols with their arrival there in 1287. Life actually appears to have carried on with little change and Pagan remained a cultural centre.)

Although Pagan may have survived the Mongol hordes and the ravages of the Second World War, in 1975, the area was hit by a huge earthquake. Some temples were totally demolished and many were seriously damaged, not least with cracks ruining many murals. Restoration work has continued intermittently ever since.

Some Monuments from the Three Periods

Needless to say, in the time I had in Pagan, I was able to visit very few of its monuments. I did, however, get to see some of the most impressive. I have chosen some examples from all three periods to provide just a taste.

Early Period – Schwe-hsan-daw

Located in the middle of original Pagan and built in 1057, the Schwe-hsan-daw, or “Sacred Hair Relic” was Pagan’s first architecturally-developed stupa: in the shape of a pyramid with steep and tall terraces. Generally believed to have been built by Anawrahta, it was constructed not only to enshrine the Buddha hair relic brought back by him from his raid on Thaton, but also as a symbol of the Buddha.

Manuha

Named after the captive Mon king, Manuha, history has it that he built it, around 1060, as penance after his dharmic powers had been eliminated by Anawrahta (vii).

Middle Period – That-byin-nyu

Thought to be one of Sithu I’s last great constructions and executed towards the end of his rule (around 1150), That-byin-nyu (“the Omniscient”) epitomises Pagan’s Middle Period. Whilst monumental, it is also both experimental and innovative. The English scholar of Pagan, G H Luce describes it thus: “This is no lifeless pile of brick and plaster. It is the Purha, the Buddha, exhibiting the great miracle. See the deluge descending from his shoulders! See the holocaust ascending from his feet” (viii).

Late Period – Mingala-zeidi

This temple was the last large-scale such building in Pagan. Built by Narathihapati (1255/6-1287), it was completed barely a decade before the Mongols entered Pagan in 1287. But its very completeness, perhaps, gives the lie to Pagan being an empire in decline facing the Mongol hordes. Indeed, writing about it in the early 20th century, Taw Sein Ko, founder of the Pagan Archaeological Museum and considered Burma’s first archaeologist, believed it to be the acme of Burmese religious architecture.

With the difficulty in obtaining any news from Myanmar, it’s difficult to know just how much damage was inflicted on Bagan in the earthquake on 28th March this year. Or, during, the current civil unrest. One can only hope.

© 2025 Tom Butcher

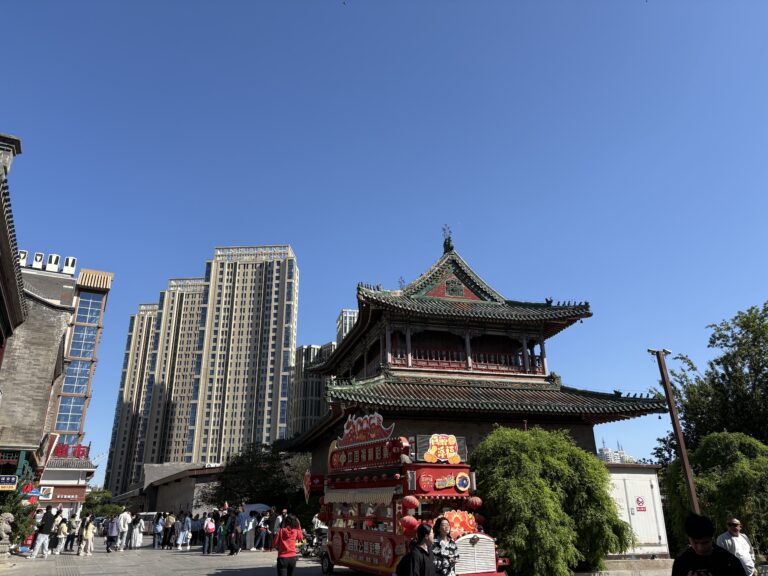

*title image – view of Pagan with That-byin-nyu Temple.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.

Notes –

- (i) The government’s actions around the Kyat domestically were often not only capricious, but also mystifying. Whilst, on 3rd November, 1985, with no warning, the government had demonetised all 50/- and 100/- kyat bank notes, the justification being to stymie black marketeers who had hoarded large amounts of cash, barely two years later, on 5th September, 1987, the government also demonetised the 25/-, 35/- and 75/- kyat notes with neither warning nor compensation, nor, indeed, explanation. The move effectively rendered worthless around 80% of the money then in circulation in Burma. Arguably, the ensuing economic hardship and chaos were the precursors to the unrest that led to the overthrow in August 1988 of General Ne Win’s 26-year one-party military dictatorship and the establishment of the SLORC (State Law and Order Restoration Council) military government under General Saw Muang.

- (ii) As my friend Paul Strachan subsequently described it: “They were moved to a peripheral location in the desert like plain with neither water nor electricity and had to make temporary shacks using materials dismantled from their former homes.”

- (iii) Strachan, P, Pagan – Art and Architecture of Old Pagan, Kiscadale Publications, Scotland, May 1988

- (iv) A stupa, or pagoda, is a solid construction containing either a sacred relic or powerful image of the Buddha. A temple, called in Burmese a guu (cave) should be understood as being, in essence, an artificial cave and, therefore, with an open interior.

- (v) Ibid, and; Pe Maung Tin and Luce, G H, The Glass Palace Chronicle of the Kings of Burma, London, 1923.

- (vi) Strachan, P, Pagan – Art and Architecture of Old Pagan, Kiscadale Publications, Scotland, May 1988.

- (vii) Ibid

- (viii) Luce, G H, Old Burma-early Pagan, Locust Valley, New York, 1969. Vol. I, p. 417.