Looting the Silk Road: the re-discovery of Dunhuang

Sean Paterson is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society living in Guangzhou

A small town in Gansu is having something of a moment. Dunhuang, famous for its treasure-troves of Buddhist art and hoard of ancient manuscripts, and for the underhanded way that foreign adventurers pilfered huge quantities of both, is back in the limelight.

Last autumn, anyone passing through London could choose from not one, but two, excellent exhibitions about the Silk Roads – the British Museum’s eponymous general overview, and the British Library’s dedicated display of the Dunhuang manuscript hoard. But it’s a long way from the Gobi to the Euston Road. How exactly did Silk Road treasures – Sogdian merchants’ order-books, Zoroastrian scriptures, Tang jade sculptures, and a copy of the Diamond Sutra, the world’s oldest known printed document – end up in Bloomsbury, of all places?

Like many artefacts in British collections, the story of the Dunhuang manuscript hoard is a controversial one. However, it is not just a sorry tale of imperial plunder, but rather one that ends happily, with an admirable programme of international co-operation, study and cultural preservation.

For thirty years, from the 1890s to the 1920s, adventurers from Europe, Russia, America and Japan launched a series of what Peter Hopkirk called ‘long-range archeological raids’ across Xinjiang and Gansu. With a combination of hard cash, trickery, and the odd bout of outright looting, they seized vast collections of ancient materials on behalf of museums and collectors at home. Dispersed from China, tens of thousands of delicate manuscripts and hundreds of exquisite murals and statues ended up all over the world. Today, to see the best of the treasures of the Silk Road, one would have to travel between Gansu, Beijing, Xi’an, Lanzhou, London, Paris, Berlin, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Tokyo, New Delhi, and Massachusetts.

These collectors – the Anglo-Hungarian Sir Aurel Stein, the Swede Sven Hedin, the Frenchman Paul Pelliot, the German Albert von Le Coq, and the American Langdon Warner among them – became famous for their mammoth expeditions. They would vanish into the desert, coming back with wild tales of adventure and survival, weighed down with precious treasures. It was box-office gold, and they made the most of it. The western press thrilled to their stories, and their books became staples of any respectable armchair-explorer’s shelves.

Dunhuang was the final prize. Here, for a thousand years, the Silk Road left the Hexi Corridor and split in two to navigate the fringes of the Taklamakan desert. It was through oasis towns like Dunhuang that Buddhism entered China via Afghanistan. In the third century AD, just south of the oasis, a wandering monk called Lezun had a startling vision: across the sides of Mingsha Mountain, he saw a thousand Buddhas in full radiance. Inspired, he carved out a small cave for meditation.

Over the next millennium, over 735 more grottoes – some small niches, others substantial excavations as big as country churches – were carved out by devout pilgrims and decorated with statues and frescoes. Dunhuang’s Mogao Grottoes became one of the great sites of Buddhism. Here, the cultures of the Silk Road melded together: early cave decorations show a distinct Indian influence, later replaced by more Chinese styles. One statue, excavated in the late twentieth century, is distinctly Hellenic: the current best guess is that it is the work of a sculptor from Balkh, in Afghanistan, where Alexander the Great had once planted a colony. Of particular importance was the unassuming niche, not much bigger than a utility cupboard, today called Cave 17.

Here, sometime around the year 1000, an enormous collection of manuscripts was walled up and forgotten. No one is quite sure why. Perhaps it was to protect them from nomadic raiders; perhaps it was a storage room for old documents; perhaps it was a time capsule. Either way, the manuscripts waited patiently for nine hundred years, long after the Silk Road withered away and Dunhuang sank into obscurity. Then, in 1900, Wang Yuanlu, an itinerant monk who had appointed himself guardian of the grottoes, made an extraordinary discovery. Digging sand from the entrance of Cave 16, he dislodged a chunk of plaster. When the dust cleared, Wang found himself looking at a solid mass of ancient paper. Removing some for his personal study, he quickly realised he was on to something special. Among the expected detritus – account books, lost letters, and marching orders – was a treasure trove of rare documents: star charts, scriptures, and illuminated manuscripts. He knew some of the languages, but others were far beyond his ken. Clearly, this merited further investigation. Wang announced his find to other monks and merchants, and the desert telegraph did its work. Word reached the governor at Lanzhou, but he was uninterested. However, approaching from the northwest were two men who certainly were.

Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin had much in common. Both were almost unimaginably tough desert and mountain travellers in the best Victorian mould, skilled archeologists, and successful writers with dubious political sympathies. Both were repeat visitors to Xinjiang, and among only a handful of men to have crossed into the innermost reaches of the Taklamakan. Both were particularly interested in the handful of artefacts dug up by local treasure-hunters, that had reached British India via the remote consulate in Kashgar. Word of Abbott Wang’s discoveries reached them at similar times, but exact details were garbled, and no one was quite sure what could be found there. Matters were not helped by the enthusiastic efforts of a particularly productive conman, Islam Akhun, who had been meeting foreign demand for ancient manuscripts by simply making his own, throwing doubt on the veracity of any supposed hoard. This confluence of suspicions led to one of the most curious oversights in archaeological history.

Hedin was first to arrive, making it to Dunhuang in 1901 – by all accounts the first European to get there since the days of Marco Polo. However, he was in the middle of a strictly geographical expedition, and dedicated himself to mapmaking and sketching. Amazingly, he passed by the Mogao Grottoes without looking into them, just a year after Wang’s discovery. When Hedin’s reports were made public on his return to Europe, Stein – who had since exposed Akhun’s forgeries, and now thought that the Dunhuang hoard might be genuine – saw his chance.

Stein quickly drummed up funding for another of his Central Asian expeditions, and set off from his base in Kashmir. Making his way through the Taklamakan via Kashgar, he arrived in Dunhuang in 1907. At Mogao, he met Wang, who had been hawking his manuscripts to other monks and local authorities without much success. Stein, it turned out, was the ideal customer. For £170 (about £17,500 in today’s money), Wang gave Stein 24 cases of manuscripts – but, crucially, didn’t let him into the library cave to pick his own materials. Though well-versed in Central Asian languages, Stein had no Chinese, so much of the collection was meaningless to him. Nonetheless, in amongst the clutter were real treasures – including the Diamond Sutra, which Stein kept quiet about, recognising its true value. He made his way back to London as quickly as he could. Stein was feted for his ‘discoveries’ (really, Abbott Wang’s), and knighted. Lectures and books followed. The manuscript hoard went into the British Museum for sorting. But now, word was out – in Dunhuang, there were treasures to be had.

With Hedin and Stein having made their names, and Wang seemingly being willing to sell, it was inevitable that more would follow them. Dunhuang now saw two more major expeditions, by far the most damaging: those of Paul Pelliot and Langdon Warner.

Pelliot, a Frenchman who had cut his teeth in Indochina, was more of a recognisably modern scholar than a swaggering adventurer. For one, he spoke excellent Mandarin, becoming a professor of the language at only 23. This meant that, when he reached Dunhuang just a year after Stein, having learned of the Mogao hoard from his Chinese contacts, he was able to negotiate directly with Abbott Wang, and talked his way into the library cave. Stein’s haul had left a gap big enough for a man to sit in, and Pelliot now set about systematically sifting through the manuscripts, separating out the best for himself.

While Stein’s collection had been essentially random, Pelliot was able to be more discriminating in his selection. Unfortunately, this meant that he found and seized many precious documents that would have passed an ordinary treasure-hunter by. Working at ferocious speed – each manuscript received, on average, just two minutes’ attention – Pelliot sorted through the cave for three weeks before concluding a deal with Wang: 500 silver taels (£11,000 today) for his haul. However, when he reached Paris and made his report, he was accused of fraud: surely, his critics argued, no one could have found, sorted through, and then memorised the contents of tens of thousands of manuscripts in less than a month, let alone bought them home intact. Islam Akhun and his successors were up to their old tricks. Stunned, Pelliot fumbled his response, until help arrived from an unlikely ally – Stein himself, who confirmed the details of Pelliot’s report with his own books. But by now, the manuscript hoard was nearly gone. What else was there to take from Dunhuang?

Sadly, there was more damage to come. Towards the end of the Russian Civil War, White troops fleeing Trotsky’s armies made their way down the Hexi Corridor, stopping in Dunhuang. Billeted in the caves, they entertained themselves by carving on the walls, and kept themselves warm in the bitter Gansu winter with smoky fires, causing incalculable damage to the ancient murals. Word of these depredations eventually made its way to Massachusetts, and to a man often cited as an inspiration for Indiana Jones: Langdon Warner.

An expert in Chinese art, Warner decided that it was time for an American to get a piece of Dunhuang, before it was accidentally destroyed. London, Paris and Berlin already had mighty collections, while Japanese collectors, led by the mysterious Count Otani, had recently joined the quest. Why not Harvard? After securing funding, he set out for Gansu with a newfangled technology: a special frame that would allow him to peel frescoes off wholesale, rather than hacking them out of the rock as Hedin and Stein had done. Warner’s two expeditions to Dunhuang mark the end of a thirty-year spree at the hands of foreign archaeologists. They were also the most damaging – his high-tech glue backfired and destroyed many of the murals he was after – and the most like outright looting. They were also the least successful. Having previously tolerated the foreign adventurers who came to their town, by the late 1920s the farmers of Dunhuang had had enough. On his first expedition, Warner found labourers hard to come by; on his second, he was pelted with rocks and chased out of town. The authorities in Lanzhou finally came down hard: from now on, anything found in Dunhuang would stay in China. Warner went home nearly empty-handed, the last of the adventurers.

The end of foreign looting was not the end of Dunhuang’s troubles, however. Thirty years of damage needed fixing, but resources were not easily available during the years of civil war and Japanese invasion. The desert did its work, and by mid-century, the caves were in critical condition. However, just in time, preservation work began. A team of scholars led by the artist Wu Zuoren arrived in 1941 to copy the murals in case of destruction. Among the team was the painter (and later, master forger) Zhang Daqian, who made his own discreet repairs. In 1944, an academy dedicated to the caves was established. Its work carried on after the Revolution, and by the 1950s it had attracted the attention of premier Zhou Enlai, who quietly ensured a steady supply of funding and resources.

In 1963, a young woman arrived at Dunhuang. Fan Jinshi, a fresh graduate of Peking University, would spend the next fifty years there, eventually becoming director of the Dunhuang Academy, and the world’s leading expert on the caves. During her time at the grottoes, the mission of the Academy’s archaeologists turned from restoration to stabilisation and preservation. A half-century’s dedicated work saw amazing result. When she first came to Dunhuang, Fan found a remote town with no electricity or running water. By the time of her elevation to head of the Academy in the late 1990s, the caves had been stabilised. She fought against a misguided attempt to turn Mogao into a theme park, and oversaw the creation of a sensitive museum instead. Under her aegis, a daily visitor limit was introduced, and the Academy began the digital scanning of the caves, so that as the frescoes decay, they will be preserved in cyberspace instead. Despite retiring in 2014, Fan still lives most of the year in Dunhuang, and remains an active participant in the Academy’s work. Where Hedin, Stein, Pelliot and Warner had plundered, Fan preserved. Where they wrote thumping adventure stories disguised as archaeological tomes, her memoir, My Heart Belongs to Dunhuang, is modest, and mostly about the caves. While they lived larger than life, she kept a low profile. If it is because of men like them that Dunhuang is known, it is because of people like her that it is kept safe.

Today, Dunhuang has established an ideal balance. Though popular with tourists – they are allowed free rein of the nearby Mingsha Crescent Lake to work out their Silk Road fantasies and mess about in dune buggies – it remains a site for serious scholarship, and an outstanding example of international co-operation. The Academy has been joined by a sister organisation, the International Dunhuang Project (IDP), headquartered in London, which has worked to join up the collections taken from Dunhuang a century ago, and make them available to scholars everywhere, while promoting wider knowledge of the grottoes. While some might argue for full repatriation of the artefacts, as is becoming more common, for now the IDP has shown archaeologists and historians a new, effective way of managing controversial cases. Though acknowledging the difficulties caused by the dispersal of the Dunhuang hoard, it takes the situation as it is, rather than as it would be in an ideal world, and works to make access as fair as possible, while bringing together scholars from all over the world, and ensuring continued awareness of the caves and their treasures. In this, it is a fine ending to a story that could have easily ended in tragedy and contention. The caves are safe for the next generation.

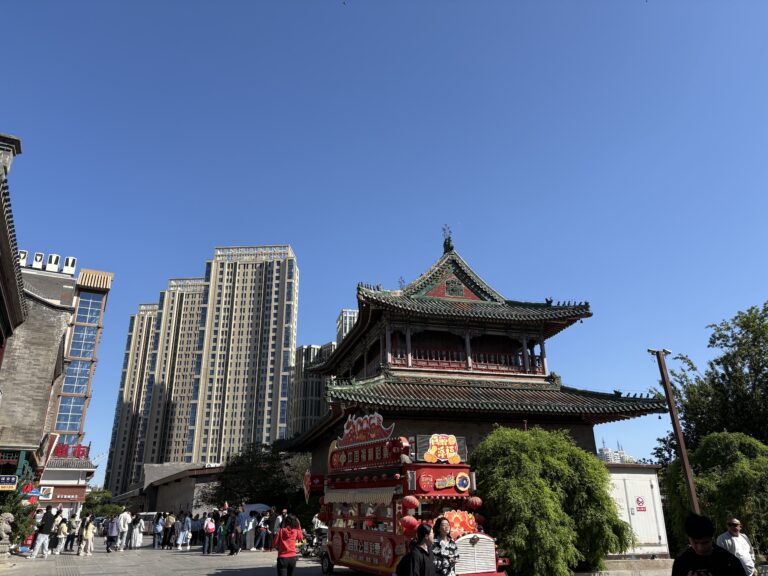

*Title image – the entrance to the greatest of the Mogao grottoes, home to an eight-storey tall Buddha statue. Similar in size and age to the famous Buddha of Kamakura, it was built on the orders of Empress Wu Zetian, China’s only female emperor. Originally, its head poked out of the roof, but it was enclosed by the time foreign archaeologists arrived.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.