South Korea’s Martial Law Peripeteia

Sung-Yoon Lee is a Korea expert and board member of The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea.

Beyond platitudes like reaffirmation of the rule of law, what the ouster of Yoon Suk Yeol – South Korea’s conservative president impeached for declaring martial law last December – illustrates is that in politics it pays to eschew excessive hubris. This moral applies to both the Yoon camp and his political foes.

Last Friday, all eight justices of the nation’s Constitutional Court found Mr Yoon had gravely violated the Constitution by sending troops to parliament purportedly to block lawmakers from voting down his decree.

Despite the sundry procedural problems throughout the impeachment trial, for example, the admission of disputed testimonies and questionable evidence, the court ruled that the totality of Yoon’s actions warrants his permanent removal from office. A poll conducted the same day when emotions were still running high indicated extreme polarity rather than unity in the aftermath of the judgment: 52.2% of those surveyed accepted the unanimous court decision, while 44.8% replied they did not.

But the public must and shall accept the ruling. A snap election will be held within 60 days amidst clashing waves of jubilation and angst.

To the approximately 56 percent of South Koreans who called for Yoon’s removal, the verdict comes as, beyond sheer delight, a great relief. Just days after declaring martial law, Yoon’s approval ratings sank to a record low of eleven percentage points. But within a few weeks they surged to the high-40s, with some even in the low-50s. What had appeared to the anti-Yoon camp a certain victory became progressively an ominous uncertainty.

Lawmakers of the main opposition, liberal Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) deserve much praise for their courage and alacrity on the night of the crisis. Just two and a half hours after the martial law announcement on the night of December 3, 190 out of 300 lawmakers – mostly from the DPK – gathered in the National Assembly and unanimously voted against Yoon’s martial law decree, making it the shortest-lived in history. Thanks to their determined efforts and the restraint exercised by the martial law troops, the volatile situation ended without a single fatality, serious injury, or physical custody.

An impeachment trial of an elected national leader is an inherently political affair; that is, its deliberation and even verdict are not impervious to the sway of public opinion. Yet, from the very next day, the DPK acted in ways strangely unhelpful to its own cause.

Instead of exercising self-restraint, Lee Jae-myung, the DPK leader, and his colleagues gloated in various public settings as they pushed for the arrest and removal of Yoon, whom they labelled the “insurrection ringleader.” To oppose impeachment was “treason against the people,” they declaimed. Posing for a group photo upon voting to impeach Yoon, they demanded “swift and severe justice.” They variously called for the death penalty, exhorted the police to take a bullet in the chest if they must in arresting Yoon, threatened to censor KakaoTalk – the most popular instant messaging app – and punish ordinary people who “share fake news about inciting rebellion.” They even sought to file a criminal complaint against a pollster that showed Yoon’s ratings had surpassed the 40 percent mark in early January.

How could an elected leader who thrust martial law on their nation – which conjures up images of bloodshed, arbitrary arrests, and torture under previous authoritarian regimes – who dispatched armed troops into the National Assembly, and who allegedly called for the arrest of key political figures possibly enjoy such a surge of support?

The DPK’s unbound imperiousness.

The party overreached at every turn. It called for Yoon’s arrest. Following a failed attempt in early January, law enforcement authorities marshalled some 1000 police officers in front of the presidential mansion by dawn on January 15. Later that morning Yoon submitted himself to their authority, as he said, to avoid bloodshed. It was history’s first arrest of a sitting – albeit suspended – head of state in a democracy.

And it spectacularly backfired. Big pro-Yoon rallies in the tens of thousands sprouted across the nation. In February, the movement also spread to Gwangju, the hotbed of anti-right, anti-authoritarian protest movements. Police estimates placed the pro-Yoon crowd in Gwangju outnumbering anti-Yoon demonstrators some 80 yards away three to one. The numbers for Yoon and his party kept rising even with Yoon behind bars. The trend continued in the wake of his release from jail on procedural grounds on March 8.

Over the past four months, more and more young male voters in their twenties and thirties shifted away from the DPK toward the right. The near-daily roars by the crowds of Yoon supporters and the shifting demographics triggered hope. All that was needed for Yoon’s return to office was just three out of the eight justices on the bench voting to dismiss the case. It proved a chimera.

So, to the approximately 47 percent of the population who support Yoon, the court decision carries elements of an Aristotelian peripeteia, a stunning reversal of fortune. At first, most of them, too, were stunned by the live televised martial law declaration. Yoon mentioned “pro-North anti-state forces” within South Korea but offered no riveting details. Yoon dwelled on the DPK’s “legislative dictatorship” with its 22 impeachment motions, just two and a half years into his single five-year term, but did not clearly articulate their implications.

By and by, the public came to learn 14 of the 22 impeachments had been waged against senior prosecutors, some who had led criminal investigations against Mr Lee, who faces numerous criminal charges, including a conspiracy and third-party bribery charge of paying $8 million to North Korea. Since the founding of South Korea in 1948 to the launch of the Yoon administration in 2022, there had been all of 21 impeachments.

While “anti-state” organisation or forces sound awkward, they are legal terms in the National Security Act that refer to individuals and groups conspiring with North Korea against the South Korean government. During the trial, Yoon’s defence addressed the extensive collusion between the leaders of the South’s Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) and the North Korean regime.

The 2024 KCTU espionage case judgment shows that between 2017 and 2022 there had been 102 confirmed exchanges between the two sides, including 90 written instructions by North Korea. KCTU leaders, on Pyongyang’s directives, had collected intelligence on how to block electricity supply to the presidential office. They had illegally taken photographs of Camp Humpherys U.S. Army Base and Osan Air Base. Yoon’s defence also showed a high level of correlation – and in some cases verbatim wording – between Pyongyang-directed anti-Yoon political slogans and those actually used by the DPK to denounce Yoon following Japan’s 2021 announcement to release the Fukushima nuclear plant treated water and the 2022 Halloween crowd crush.

Thus, had it not been for Yoon’s December national wake-up call, his supporters say, most of the country would still be in the dark about the DPK’s machination. Lee’s public thanks to the KCTU chairman in February for “KCTU members playing the biggest role in the impeachment of Park Geun Hye and Yoon Suk Yeol” also raised eyebrows.

Whether Lee was exaggerating or not, the situation today does have parallels to the impeachment and ouster of the conservative party’s President Park in 2017. Back then, nearly 80 percent of the Korean population supported her impeachment for abuse of power. Today, the national divide following Yoon’s political demise is much more acute. The bitter division reflects to a substantial extent the perceived excesses of the DPK even in achieving its goal of removing Yoon from office.

Beyond the unrelenting zero-sum domestic politics, South Korea’s treaty ally, the United States, and other friendly nations around the world are likely less than overjoyed at the ruling. After all, Yoon had repeatedly affirmed his support for the alliance with the US and the rules-based international order. Whereas Lee has denounced his nation’s defensive military drills with the US and Japan as an “extreme pro-Japanese act” that is a “defence disaster,” Yoon has determinedly underscored the trilateral military partnership.

Ukraine, too, may not be elated. Lee has openly derided President Volodymyr Zelensky as a “novice politician of six months” who incited Russia’s invasion. He has also strongly objected to South Korea even considering sending any non-humanitarian aid to Kyiv, while Yoon has provided economic and material support and pledged more in both value and kind. Accordingly, the leadership’s in Pyongyang, Moscow, and Beijing may not be displeased by Yoon’s downfall.

Among the many morals of this real-time, monthslong Korean drama, one surely is that in politics, hubris and solipsism only beget blunders both big and small. And the more elemental truth? The growing voice of the people – especially when it pours forth day after day like the rolling waves in the rough sea – commands respect.

Yoon, for all his follies, exits the political stage with one of the highest approval ratings of his truncated term, in no small measure thanks to his political adversaries. Who succeeds him and in which direction the vicissitudes of political fortune take the Republic of Korea in the next few years remain, for better or worse, a story still to be written.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.

More from this author –

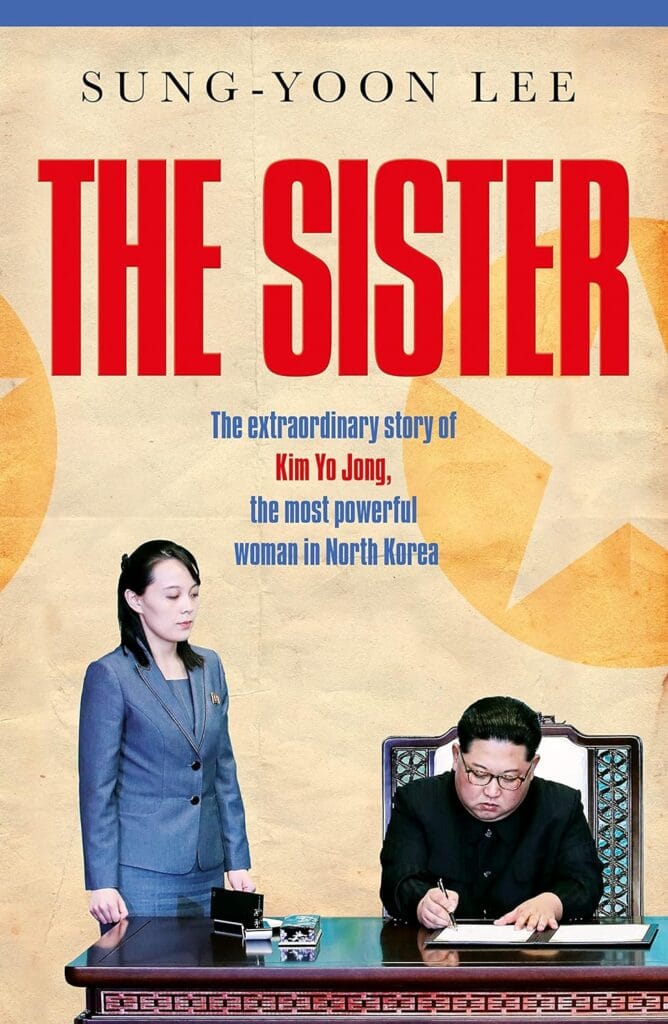

The Sister: North Korea’s Kim Yo Jong, the Most Dangerous Woman in the World

This book uncovers the truth about Kim Yo Jong, sister of Kim Jong Un, her close bond with her brother and the lessons in manipulation they learned from their father. It examines the iron grip the Kim dynasty has on their country, the grotesque deaths of family members deemed disloyal, and the signs that Kim Yo Jong has been positioned as her brother’s successor should he die while his own children are young.