Pakistan’s Global Image: Perception and Causes

Nadir Cheema is an academic at the School of Oriental and African Studies and UCL, University of London. He specializes in economics and studies Pakistani socio-political issues. He is also a senior fellow at Bloomsbury Pakistan.

The perception that Pakistan lacks credibility within the international community is a common one among analysts and academics working on the region.[i]

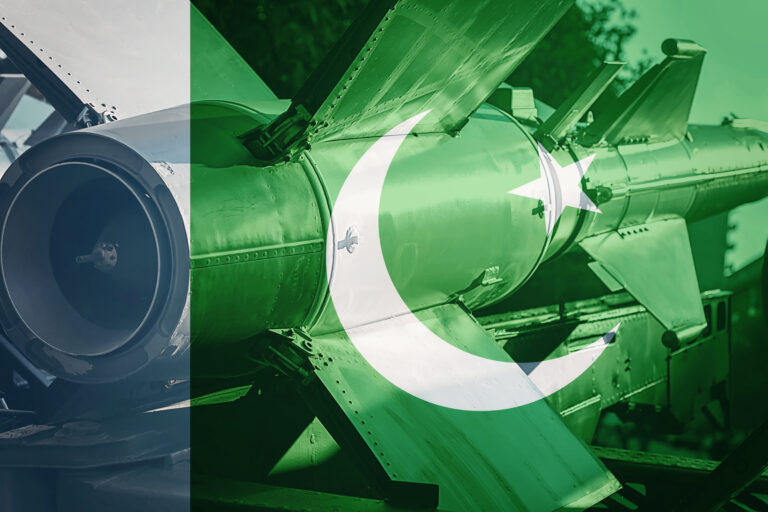

A survey, conducted exclusively for this article, set out to examine the nature and origins of such negative views about Pakistan. Members of the Foreign Service Programme class of 2016 at the University of Oxford, mainly comprised of diplomats from all over the world,[ii] were asked ‘what three things come to mind when you hear about Pakistan?’ The majority of respondents cited nuclear weapons, terrorism, security, Islam, and the Taliban, lending support to the general view of Pakistan as a militarised state involved with Islamic extremism.

Pakistan has paid an enormous price for being the frontline state in the war on terror. It lost around 80,000 lives (50,000 civilians, 6,000 security personal and 27,000 militants) during the US-led ‘war on terror’ between 2004 and 2013.[iii] But despite its sacrifices, Pakistan is perceived by the West as a treacherous ally that shamelessly promotes Islamic radicalism.

Pakistan faces enormous challenges, ranging from an unbalanced economy, fragile governance and security to rampant terrorism. But perhaps its greatest challenge is to restore its credibility in the eyes of the world. The establishment’s efforts[iv] to project a positive image of the country have had little impact. The question arises whether Pakistan’s establishment understands the root cause of the problem. In Foucault’s phrase, the world’s perceptions of Pakistan “have been made; they can be unmade, as long as we know how it was that they were made.”[v] The process must begin by discovering how these perceptions came about; then, once we know how they were made, unmaking them.

Countries are, at least in part, judged by the nature of their foreign policy. Pakistan’s foreign policy is largely a function of its national security doctrine, which has the perceived threat from India at its core. Foreign policy is thus driven by objectives articulated and defined by the requirements of national security.

The security narrative, broadly speaking, adopts a unitary outlook on the world, prioritising one nation, one set of values and one national tradition. Defying this unitary approach, refusing to conform to it, leads to immediate stigmatisation. It is a process that undermines pluralist society and discourages the projection of a nuanced, realistic picture of the country. It irons out diversity and necessitates conformity.

The security narrative that permeates Pakistani society to such an extraordinary degree relies on a very rigid definition of national interest. Dr. Farzana Sheikh, a fellow at Chatham House, claims that, “There is no understanding of the national interest as the one that might encompass larger issues of social and economic welfare. It projects the image of the country that is primarily concerned with the defence of its frontiers and the questions of democracy are subordinated to questions of sovereignty.”[vi]

The security narrative manifests itself as a defensive form of Pakistani nationalism. It has created an imagined community, in terms defined in social theory by the sociologist Benedict Anderson, that belongs to different geographies but has a sense of belonging to a particular idea.[vii] Similarly, the Pakistani establishment, institutions and large sections of population, are convinced by the narrative of the security state and the belief that Pakistan is surrounded by hostile powers such as India, Afghanistan and Iran. The outside world is perceived as conspiring against it. With the cohesive bond of religion seemingly holding them together, the class interests of various groups are aligned to produce a potentially explosive version of this nationalist narrative.

Despite the emphasis on the security narrative, Pakistan has not been able to achieve the strategic relationship with the West, particularly with the USA, that it covets. Efforts have been made to make the relationship a strategic one, but it remains at best transactional and tactical. As Raza Rumi, a scholar at Ithaca College and Cornell University, strikingly puts it:

‘It is like you give me million dollars, I give you location of militants and you drone them. You give me F16s, I will deliver you ‘X’. A kind of a supermarket security grocery shopping.’[viii]

The dominance of the security establishment is not the only reason for Pakistan’s negative perception in the world. The political parties are in disarray. With virtually no internal policy thinking, they are not equipped to reflect on the larger issues of security and foreign policy. Consequently, when civilian regimes have been in power, particularly since 2008, they have been unable to make any appreciable impact.

The relationship between the government of Pakistan and the international media has been problematic to say the least. The spread of social media has undermined the government’s monopoly on information and made information sources difficult to manage. The state may continue to intimidate local Pakistani media organisations, but this is quickly picked up by the global media, through their correspondents’ close ties with local media houses.[ix] Pakistani officials are convinced that the international media focus on negative aspects of Pakistan and have a preconceived mindset that negative stories on Pakistan sell better. There may be some truth to this argument. But the establishment’s obsession with it can mean the root causes of genuine problems are not addressed, further damaging the country’s image.

Pakistan’s Foreign Office lacks institutional capacity, as discussed in Cheema (2015);[x] it is a fossilised organisation relying far too heavily on old school diplomacy, while failing to adopt modern tools of international influence, such as cultural, public and economic diplomacy.

There is a growing consensus against Pakistan in the global think tank industry of Western countries. There is an urgent need to address this. But the prevailing nationalism in Pakistan, narrowly defined and lacking depth or subtlety, promotes intolerance of critical debate in the country. Academics and other members of the intelligentsia who engage with global think tanks are labelled disloyal or anti-state. The establishment is unable to recognise that critical thinking is a necessary and beneficial feature of academic debate. It fails to acknowledge that academics who critique state policies are doing so for the wellbeing of society and in order for the state to perform better. They are far from unpatriotic.

Pakistan’s current mode of foreign policy, driven solely by the demands of a perceived external security threat, is untenable. It must redefine its national interests to include issues such as social and economic welfare. The present paradigm of national security is too narrowly drawn and must be replaced by one that embraces the needs of human development as the basis of domestic and foreign policies. Having an educated, healthy work force with well-trained human resources for the future economic growth of Pakistan is vital. In order for the country to flourish in all its complexity, in order for a more nuanced, more realistic picture of Pakistan to emerge, the military must take a step back. The establishment must allow the country to experience and evaluate a range of opinions that are currently not available to it. If the establishment persists in trying to project the distorted values it has so far espoused, it will deeper entrench Pakistan’s negative image abroad and damage its credibility even further.

Footnotes:

[i] Private interview with twenty-five analytics and academics working on Pakistan between May – August 2016.

[ii] Survey from Foreign Service Programme class 2016 at University of Oxford, facilitated by Dr. Adeel Malik on 8 June 2016. Participants 12; women 4, men 8 representing nine nationalities (USA, Japan, Britain, Poland, China, South Korea, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan)

[iii] (2015) “Body Count: Casualty Figures after 10 Years of the War on Terror” by PSR: Physicians for Social Responsibility (US American affiliate), Washington DC, PGS: Physicians for Global Survival (Canadian affiliate), Ottawa of IPPNW (International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War) http://www.ippnw.de/commonFiles/pdfs/Frieden/Body_Count_first_international_edition_2015_final.pdf

[iv] Definition of establishment as used in UN Report (2010) ‘’Report of the United Nations Commission of Inquiry into the facts and circumstances of the assassination of former Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.’’ Page 6. http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/Pakistan/UN_Bhutto_Report_15April2010.pdf

(Establishment: “the de facto power structure that has as its permanent core the military high command and intelligence agencies, in particular, the powerful, military-run the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) as well as Military Intelligence (MI) and the Intelligence Bureau (IB). The capability of the Establishment to exercise power in Pakistan is based in large part on the central role played by the Pakistani military and intelligence agencies in the country’s political life,…”)

[v] Kelly, M. (1994) ‘Critique and Power: Recasting the Foucault/Habermas Debate’ (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press), 127.

[vi] Private interview with Dr. Farzana Sheikh, Fellow, Chatham House Royal Institute of International Affairs. 26 May 2016.

[vii] Anderson, B. (1991), ‘Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism’ Verso

[viii] Private interview with Raza Rumi, Scholar in residence at Ithaca College and teaching at Cornell University. 19 June 2016.

[ix] For instance the incident of Pakistani journalist Cyril Almeida picked up by the international media on 11 Oct 2016. http://www.wsj.com/articles/pakistan-bars-journalist-from-leaving-the-country-1476185599

[x] Cheema, N. (2015), ‘Impediments to the Institutional Development of Pakistan’s Foreign Office’. George Town Journal of Foreign Affairs. http://journal.georgetown.edu/impediments-to-the-institutional-development-of-pakistans-foreign-office/