From Osh to Dushanbe: Along the Silk Road

Christopher Wilton-Steer is a travel photographer, writer and the Global Lead for Communications at the Aga Khan Foundation

There were perhaps 300 people waiting to cross at the Uzbek-Kyrgyz border. I estimated a six hour wait time. But, as elsewhere in Central Asia, as soon as I – a tourist – was spotted I was sent to the front of the queue; a level of hospitality I really did not feel worthy of.

On the other side, some colleagues from the Aga Khan Foundation were waiting for me. AKF – a charitable foundation working to improve the quality of life of disadvantaged and often remote communities – works extensively in Central Asia so I had arranged to photograph some of our projects on this leg of the journey.

Unlike arid Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan is mountainous, lush and green. It cannot compete with the riches of Uzbekistan’s architectural heritage but it more than makes up for this with its jaw-droppingly beautiful landscapes. It is a nation of vast, gentle and sweeping valleys and, in places, still appears a land before time. The sense of space, under the huge dome of the blue sky, is profound and the experience is spiritual. I’ve visited very few places on earth that feel like genuine wildernesses, this is one of them.

Nowhere was this more keenly felt than at Son Kul, an enormous plateau atop the Tien Shan Mountain range. To reach it you must drive about two hours south from Naryn and then up winding roads into the mountains.

Eventually the road flattens out and the shimmering blue lake of Son Kul appears over the horizon. Thousands of horses, sheep, cows, yak and even camel dot the landscape. They are herded by men on horses, wearing traditional Kalpak hats.

White yurts, the homes of these semi nomads, can be seen in distant valleys; their impact on the environment negligible and ephemeral. The sense of isolation here is magnificent. My colleagues and I spent the day walking, each of us in a different direction. This sublime landscape is best enjoyed alone and the experience is meditative.

Sunset turns the sky, land and lake brilliant oranges and pinks. Grazing horses cast long shadows. At night it is very cold. After hot soup and a plate of Lagman (noodles with vegetables and beef), I went to bed in my yurt. Even in my clothes, a sleeping bag, and wrapped in a duvet, I feel the chill. A man arrived at 6am to fire up my stove. Through blurry eyes, I watched his face glow and the fire grow. Warmth, at last, returned.

I spent the early morning in the saddle exploring the lake. Horse-riding in this region dates back millennia. Babies still learn to sit in the saddle before they can walk and by their late teens young nomads will have developed advanced riding skills.

Nestled in a valley in the Tien Shan mountains, is the remote town of Naryn. Amongst the unremarkable buildings that make up this town, you can find a most unexpected sight; one of the state-of-the-art campuses that make up the University of Central Asia. UCA was founded in 2000 by the governments of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan in partnership with the Aga Khan Development Network. Its mission: to help develop the region’s future leaders, promote its social and economic development and enable its communities to preserve their rich cultural heritage as assets for the future. All three campuses are located along the old Silk Road trade routes and about 200km from the Chinese border. The hope is one day that this small town will become one of Central Asia’s great university towns.

From Naryn I returned to Osh and began my journey to the Kyzyl-Art pass where I was to cross over to Tajikistan. Unbeknownst to me, 20km of no-man’s land separates the two countries. The broken road that connects them rises to 4,200 metres above sea level and the temperature drops to near freezing. I think this is what the driver was anxiously trying to tell me in Kyrgyz two hours into our journey to the border. That, and that he had forgotten to bring his passport and so would be leaving me to take the mountain road to Tajikistan alone.

Fortunately, a couple of hours into my walk to the Tajik border, two adventure motorcyclists from Germany passed by. They kindly offered to ferry me to the border and I was soon on my way into the Pamirs and onto the roof of the world.

_____

The far eastern part of Tajikistan is a desolate place. It is dry, dusty and lunar like. Very little grows there. The air is thin. A short walk from the car had me gasping for breath.

Unlike the rockier Pamirs to the west that burst out of the earth’s surface in dark browns and deep ochres, the mountains here are softer and glow purple, pink and blue.

My first stop was Murghab, the eastern anchor of the Pamir Highway — the historic road and trade link that traverses Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Murghab was founded by the Russians in 1893 as their most advanced military outpost in Central Asia. At 3,650 metres above sea level, it is the highest town in Tajikistan. Due to its altitude and remoteness, only a few thousand people live here. In the summer months, semi-nomadic Kyrgyz bring their yak to graze in the nearby pastures and retreat to the town during the bitterly cold winter months when it can reach -24℃.

Huge trucks roll through Murghab from China’s frontier. They will travel thousands of kilometres, braving treacherous mountain roads, to ferry goods to Dushanbe, Tajikistan’s capital, and beyond.

Parallel to the Pamir Highway is an endless chain of telegraph poles. They once carried the only communications link between Mughab and the outside world. Built by the Soviets in the 1950s, the poles still stand proudly for hundreds of kilometres even though their original use has long since passed.

“Everything good about Tajikistan came from the Soviet Union,” says Igor one of my travel companions. His younger colleague comically rolls her eyes but I understand his point. Schools, hospitals, roads, energy networks and more were invested in by the Soviets, even in this most remote corner of their empire. Across the border in Afghanistan and beyond the Soviet sphere of influence, there is nothing like this. Barely a light can be seen at night.

However, following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and an ensuing civil war, this mountainous region suffered a humanitarian disaster. At its worst point, only 13% of the population had access to electricity. In the intervening years, great efforts have been made by agencies of the Aga Khan Development Network to restore the energy infrastructure and improve access to energy. In Deh village, I spoke to a woman who, like many Tajiks, had migrated to Russia in search of work. Why, I enquired, had she and her family returned to the Pamirs. “It’s simple,” she said. “Now we have electricity.”

To continue our journey, we took the Ghudera pass; a frighteningly narrow road that clings to the edge of the steep mountains. After several hours driving, the valley floor opens out spectacularly into the Wakhan Corridor. Next to the river basin, farmers harvest fields of wheat and potatoes; the latter this region is famous for.

Once a thriving corridor along the Silk Road, the valley is dotted with the ruins of stupas, forts, caravanserais, and palaces. The best preserved of these is the fortress in Yamchun, also known as the Fortress of the Fire Worshippers, which sits majestically overlooking the Wakhan Corridor. Dating back to the 3rd century BCE, this crumbling fortress once guarded the trade route to the north of the river Panj and, some believe, provided a place for Zoroastrians to pray.

In Khorog, I enlisted the help of a guide from the Pamir Eco-Culture and Tourism Association to show me around the area. From the summit of Khorog Peak, I could see the Panj river and, beyond it, Afghanistan.

Six bridges cross the Panj which marks the border between the two countries. They were constructed by the Aga Khan Foundation to help improve connectivity and economic opportunities between these historically linked regions. I had planned to cross one to enter the Wakhan Corridor. My proposed trip, however, coincided with elections (September 2019) so travel to Afghanistan was restricted on security grounds.

With Afghanistan off limits, I would need to travel several hundred kilometres by road to Dushanbe then fly via Dubai to reach Pakistan, a mere 50km away as the crow flies. I had hoped to avoid flights altogether but this one I had to take.

Christopher’s professional and personal work take him to remote and off the beaten track locations across Africa, Asia and the Middle East. His photography explores less well documented and often misunderstood parts of the world in an effort to build bridges of interest and understanding between distant cultures and bring attention to diminishing cultures.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributor, not necessarily of the RSAA.

From this author –

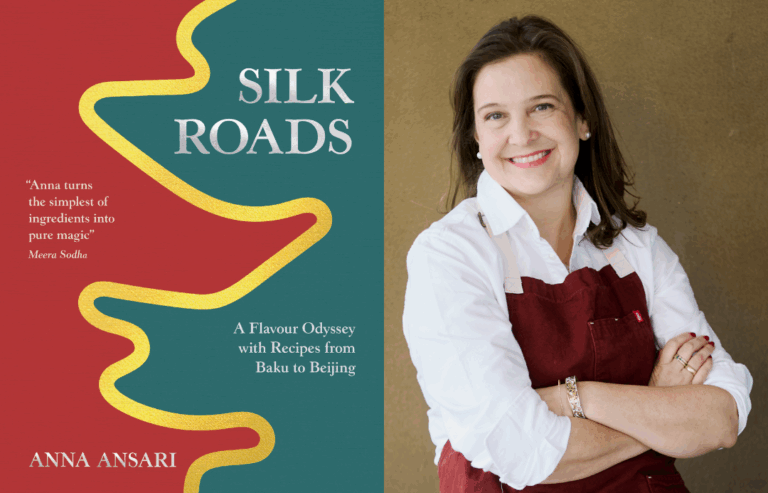

Read more about Christopher’s travels in The Silk Road: A Living History, published by Hemeria and in bookshops in late May 2025.